Victor Goines on “Quarantine Blues”

Victor Goines

A month ago, Jazz at Lincoln Center (JALC)—under the leadership of Managing and Artistic Director Wynton Marsalis—released “Quarantine Blues” arranged and performed by members of the JALC Orchestra, each from their own homes. In jazz, collaborative leadership is a given, but this was a unique musical and technological challenge.

The idea sprang from Victor Goines, a long-time member of the orchestra’s woodwind section, who also serves as the Director of Jazz Studies at Northwestern University in Illinois.

We spoke with Victor by Zoom to discover more about how this collaboration worked and the lessons he’s learned during this pandemic moment. Here are edited excerpts:

Thanks for taking the time to speak with us, Victor. How you been, man?

I’m busy. It’s a different kind of busy. I know many people who thought they’d be lounging at home, not doing anything. Now you’re doing twice as much because you have to generate stuff out of thin air.

How does that show up for you? What have you been doing?

I’m at Northwestern, teaching, so I have classes multiple times a day. In fact, for the students, I’m more accessible now because I’m stationary

And Jazz at Lincoln Center—I’m doing a lot of stuff there. We have great leadership there that allows us to stay active and present in the moment. I think that’s the key to survival afterwards, to not get lost inside of all of this Covid problem.

How would you describe the leadership there?

Greg Scholl, the Executive Director, as a leader, is very present, though I don’t have a day-to-day kind of working relationship with him.

As soon as social distancing came, he and Wynton got together to map out a plan to keep the organization intact. For both of them, it was important for us as an organization to stay together to move forward in these troubled times.

How long have you been in the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra?

It’s going into the 27th year, since 1993, when I also joined Wynton’s septet.

And how long have you known Wynton?

I’ve known Wynton since we were in kindergarten together in New Orleans, in the 7th ward.

After kindergarten, there wasn’t much interaction until we became involved in an elementary school group called the Jesuit Honor Band. We were probably in fifth or sixth grade at the time. They would audition people from around the city. I made that band, Wynton made it, Branford [Marsalis] made it.

From that point on, we’ve been in touch.

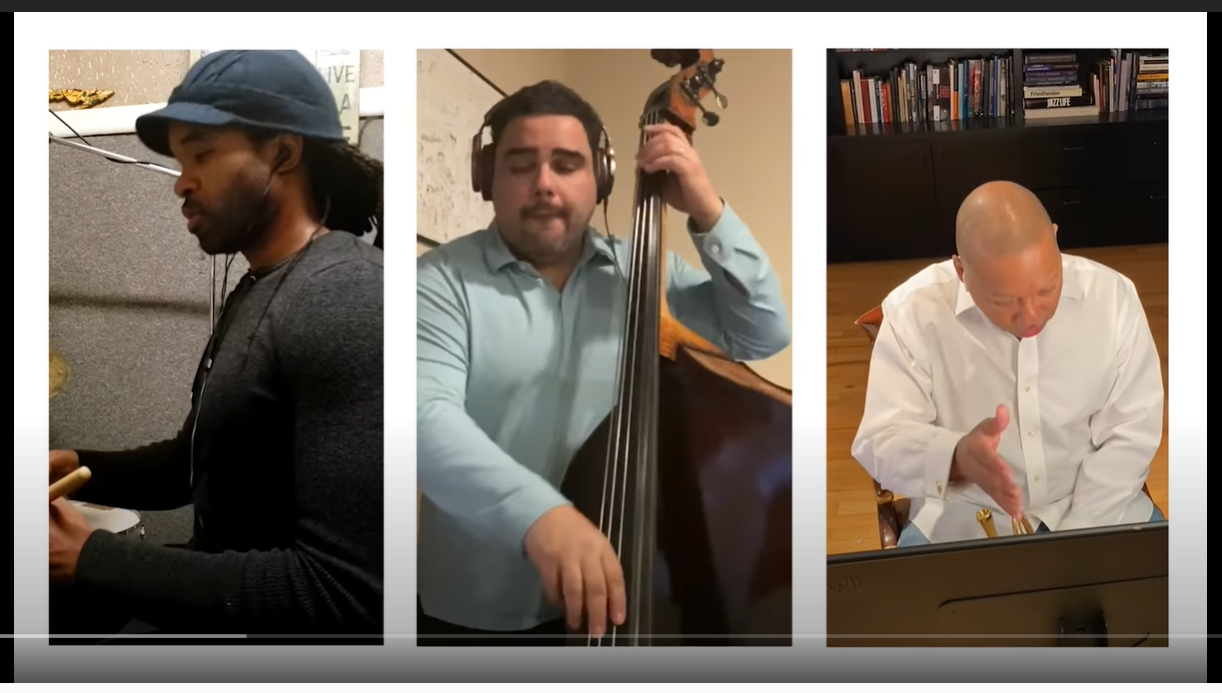

Opening image from “Quarantine Blues”

How did “Quarantine Blues” come about?

I was having a casual conversation with Wynton. I said: “Man, we need to record something together.”

He said: “How would we do that?”

“Everybody would record their part, and the engineers would put it together, like overdubbing, and we’ll have a piece.

He said: “Alright. Well, you write the first chorus.”

[Laughing] That’s a typical Wynton thing: Alright, let’s do it, you do it first.

A day passes, and Wynton asks: Where’s the blues?

I hadn’t done it yet. I had other things I was doing too.

He said: “Well, I’ll write the first chorus.” He sent it to me that night. The next morning, he says “I did mine, where’s yours?”

I can appreciate leading by example, so I sat down and wrote my chorus.

Then we passed it to Ted [Nash], and it kept going through the line of people.

To me, the idea of a great solo is one that is continuous throughout the entire ensemble. So, I wrote my own for the first 8 bars, and put Wynton’s last four in mine.

Then Ted did something similar. It kept going like that for 4 or 5 choruses, until we got to the Latin expert, our bassist Carlos Henriquez; we call him “Mr. Clave.” He went right to his heritage, which is good because if you’ve had the same groove for a while, it’s time for another groove.

Then it continued in a swing vein, until we got to Vincent [Gardner], and he decided to modulate the key, which adds more interest to it.

We started to bring to the table what we individually express creatively, but at the same time were able to solidify it as a unit.

Was this a complex challenge?

Speaking of complexity, when Wynton sent his chorus to me, he had so much music in there, I was like: “Dude. Do I get any notes that I get to use? You used up all of the notes, man!”

It was like going a hundred miles an hour out of the gate, so I decided to slow it down a little.

I thought I ought to use some long notes. While the melody was established, I decided I wouldn’t use extensive counterpoint. So I had bigger notes for the saxophone, called balloons, whole notes, longer lines, with certain calls and responses from the trumpet section.

Wynton had a lot of notes, so I decided to go the other way with fewer notes. That was my counter-statement, to go from his more to my less.

What have been some of the lessons you’ve learned in this period?

To try to be better. My learning curve has really escalated, technologically, educationally. Learning about my students, and the things that they deal with. Learning how to better communicate because we don’t have the luxury of being in a room with each other, so if we’re going to lose some of our presence, we have to gain in clarity.

For “Quarantine Blues,” how did the order of playing work?

We decided that the drums would go first. The drums are the conductor of the band, that’s the timekeeper. So, Obed Calvaire laid down his tracks first, then Carlos, and then Dan [Nimmer] on piano.

Then we started to realize that we had to do the same things we do in a big band: follow the lead player. Now the lead players record first, for basic things like intonation. And we get a pitch from Dan right before we start.

Who was the video and editing team who put together the parts and did the editing?

I don’t know everyone involved in that, but Todd Whitelock sends back our tracks. That’s the wonderful thing about the organization: the band is the face of JALC. But Jazz at Lincoln Center is bigger than a 15-piece big band, and a phenomenal, historic big band director in Wynton.

There are another 135 employees that make us successful at what we do.

Wynton Marsalis and Victor Goines

In my blog post on Wynton’s style of leadership, which I called an “interdependent style,” I recall my observations on the way he facilitates and opens the way for each musician in the band to share in arranging and musical director duties. This is an example of what in business literature is called “shared leadership.” Can you speak on this?

There is a term that I learned recently: situational leadership, leadership by dealing with people on their own terms. He doesn’t depend on everybody to operate under the same expectations as the person sitting next to them. Some people he might expect to do more in one way than another.

That takes a great deal of understanding, of flexibility, patience, to deal with people as a situational leader.

Aside from your work with JALC, what have you been engaging in as a musician and teacher of jazz?

As Director of Jazz Studies at Northwestern, I’m engaged with that everyday from morning to night, not just from an educational point of view, but from a humane one.

I sent an email to our President and concluded by saying: “I think this is a time for us to be more human with each other.” So I try to be more human with my students to understand where they’re coming from, where their hardships are at, understanding that not only financially or even academically, but emotionally.

I’ve been writing and dealing with my instruments, as always. I want to develop some platforms for teaching inside of JALC and outside of it. The biggest challenge is myself; as they say, the key to success is getting out of your own way.

I tell people this: the greatest marketing slogan in history, in my opinion, is Nike’s—Just Do It. Then evaluate and improve upon it later, just like we do on the bandstand. You got to be willing to make mistakes, as Ellis Marsalis would say.

What advice would you have for other jazz musicians to survive and even thrive amid this pandemic?

I look at the pandemic as if it’s part of a race. It’s the human race. They key to winning is getting a good start out of the block, if not a running start. If you can be at full speed at the start, then the chances of you winning are greater unless you get fatigued and not finish.

So, for all musicians and everybody else, it’s important that we stay relevant, active, seen. We need to keep learning. So when we get back to the completeness of the human race, we’re at full speed.

Don’t start from a standstill. Stay engaged and stay in motion, so when the gun is fired again and the race continues, we’re at full speed, not standing still.