Sonny Rollins and the Heavenly Culture of Jazz

If we synthesize insights from Andre Malraux, Susanne Langer, and Albert Murray, we could say that artists transmute feeling and mood into devices of image and sound through technique and creativity, creating forms that counter chaos and entropy. That’s one reason why honoring masters of form, artistic form, is an ancestral imperative. Their example ennobles the human spirit by exemplifying how we can all become more creative and artistic in the way we live, work, and play together.

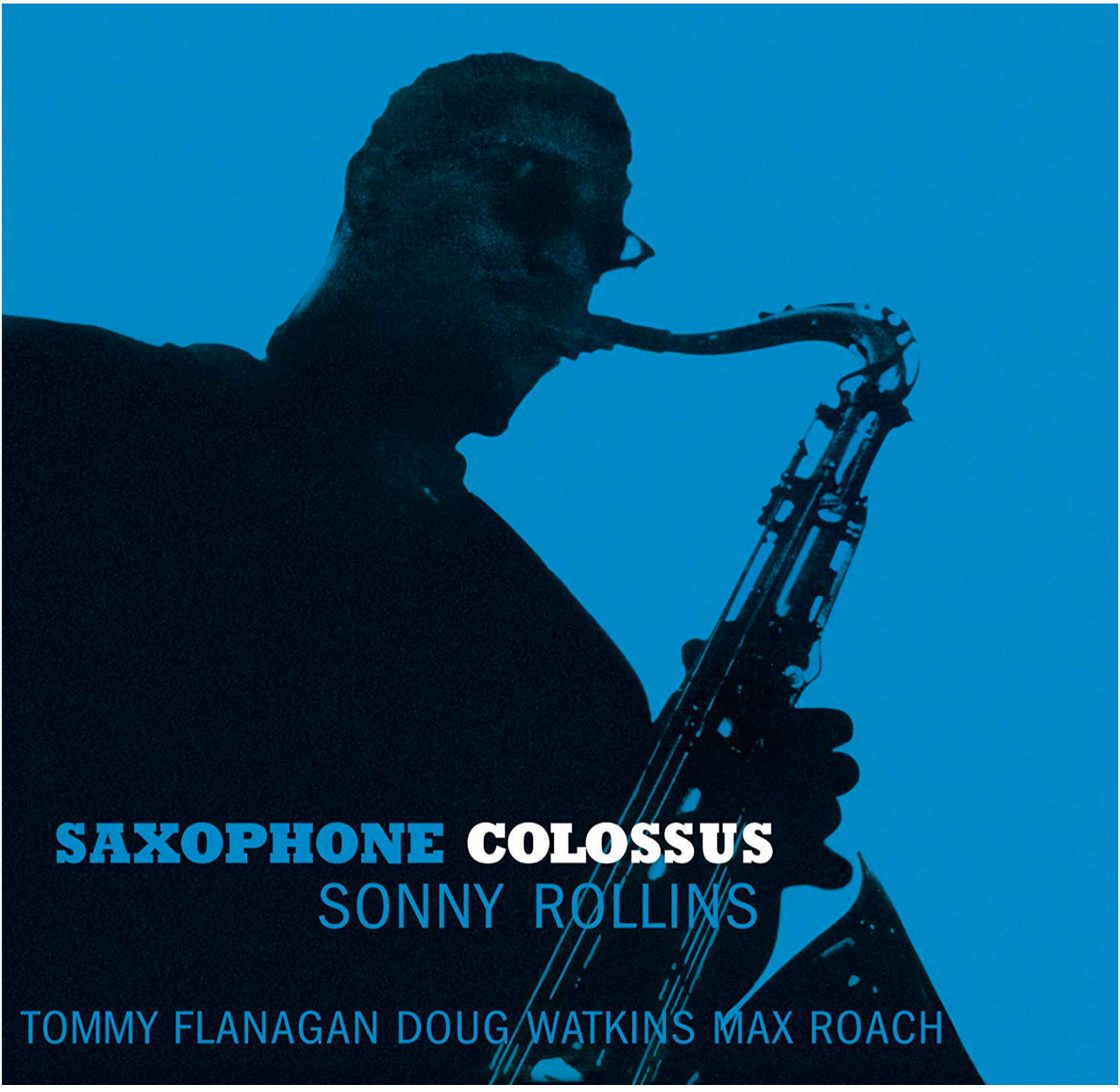

The living master of form that we honor today is Walter Theodore “Sonny” Rollins.

Conversing with Sonny Rollins as Kaya Listens

Since the 1950s, saxophone colossus Sonny Rollins has demonstrated mastery of jazz form, conquering chaos via a seemingly infinite reservoir of sui generis rhythmic swing and tenor mastery. Today we honor Sonny; he’s 91 and no longer performs in public. But his wisdom is perennial, as should be clear by this excerpt from a 2010 interview, which took place on the occasion of his 80th birthday, right before a celebratory concert at the Beacon Theater in New York City featuring Rollins with fellow senior grandmaster Roy Haynes on drums, the great Christian McBride on bass, with cameo appearances by Roy Hargrove, Jim Hall, and Ornette Coleman.

So that my daughter Kaya, now 26 years old, could hear a jazz master speak, a few days before her 15th birthday, I had Sonny on speaker phone during the following chat. Sonny’s response to my final question had Kaya awestruck, with mouth agape, as Sonny riffed: “. . . when I play my horn, I get into a state where the music plays me. I'm just standing up there and fingering my horn and blowing. See?”

Greg Thomas: My daughter Kaya is 14 years old. For her generation, what would you say is the importance of learning about and listening to jazz?

Sonny Rollins: We have to understand: we are Americans. Therefore, we're always under pressure to represent ourselves. I don't care what kind of civil rights — a black president, black secretary [of state], doesn't mean anything — we're always a minority group in America. See? As such, what we have to validate ourselves is our history, our culture, what we have done over here, where we are citizens!

But besides that, they have to understand the cultural aspects of jazz. See, this is something that allowed us, allowed her, allowed you, allowed me, to be proud of something, man. See?

Some might say, oh, gee, I'm young and I'm gonna go with the style of my peers. OK. That's fine. You know, I like all music. I'm educated enough to appreciate all kinds — hip-hop, everything. I like all of it.

But the point is that she has to understand that jazz is the umbrella for all the other black musics [in the U.S.].

GT: What keeps you going at it every day? And what kind of regimen do you have to follow to keep yourself physically fit?

SR: [Deep laughter.] Well, I've had a long life. I've indulged in everything during my life. So, when you talk to me, you're talking to the voice of experience.

See, around the 1950s I began trying to better myself. I began reading a lot then. I started to realize that I had to do something with my life, with my body. You know, I'm here smokin' and drinkin', till I said, wait a minute. I began getting into health foods and began to understand that what you put in your mouth makes your mind operate correctly.

So, in the '50s I began to get more of a foothold on, what am I doing here? Life, what is it all about? So I began to think that way, and I really cultivated some of these good habits. So maybe that's why I'm still around. I still do my yoga, I still practice my horn every day. And I'm still the same person, it's just now I'm 80. [Belly laughter.]

GT: What would you say about the mental/intellectual side of the music?

SR: Oh, man, that's everything. How can we deny the music of people like Scott Joplin? People talk about America. Look, man, I saw this movie one time — the cat says, well, during the first World War, the people in France thought the national anthem of America was the "St. Louis Blues"!

You know? That is America. I don't want to say, oh, black is the only — no — but the black culture did bring jazz into being. I'm not saying that nobody else can play jazz; no, I'm not saying that. I'm saying that what we did is a result of, maybe, Africa being the first continent that every other race came from. So we do have this deep propensity for music. We got it and we made it into jazz, as well as other forms of the black Diaspora.

But jazz is my thing, and I think it's the greatest music in the world. Jazz is the music of this planet, because jazz mimics nature. When you play jazz, real jazz, you don't know what the next note is going to be.

GT: Yes, sir.

SR: The next note comes just like each day is different. Like this morning, it was cloudy and rainy; now the sun is out up here where I'm at. That's jazz. It's like nature. There's no other music like it.

GT: When you equate jazz with nature, there's also human nature, us being emotional beings. Talk about jazz and emotions, feelings. You felt it.

SR: I felt it! You felt it. Man, that can consume you, just listening to that kind of energy and creativity, see, and the power of that music. And that would go through other great artists that we've had all through the years. This music is the greatest, and that's why they can't stop it. They always say jazz is dead. Jazz ain't dead. You can't kill jazz! It's not a person that you can kill.

GT: It's a part of black American culture, it's part of American culture, it's part of world culture.

SR: It's a part of world culture, and it's a part of … heavenly culture.

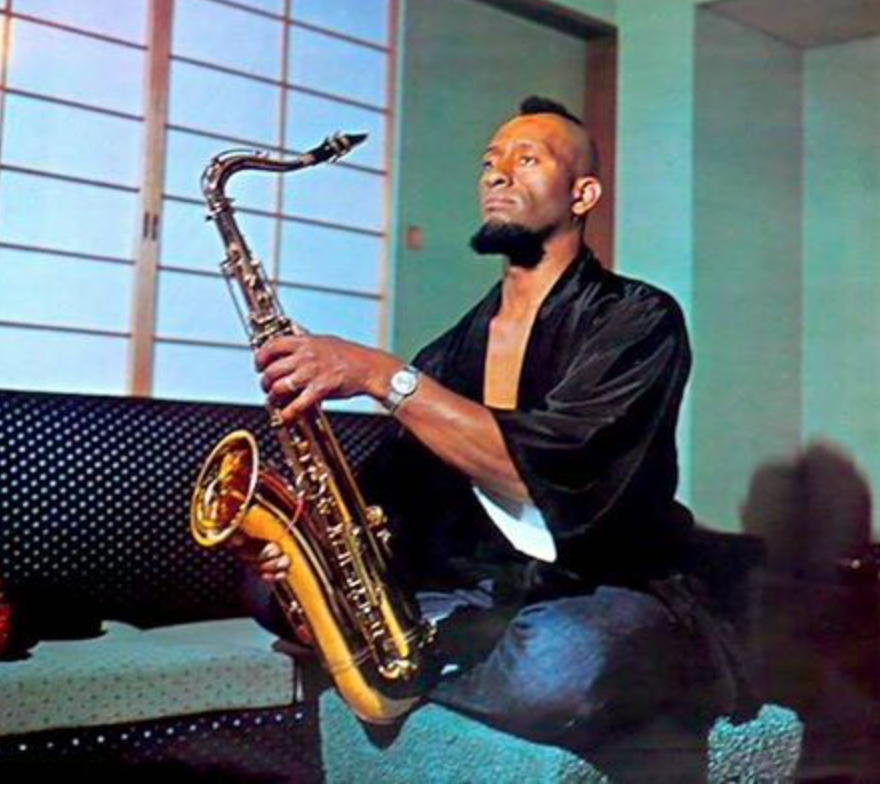

GT: Talk about jazz and the spiritual dimension. You've studied yoga, you even spent time in Japan and India. Riff on that aspect of jazz.

Sonny Rollins in Japan

SR: Somebody was asking me recently—Sonny, when you were getting into yoga, what connection did that have to jazz?

I said, I'll tell you one connection. Once I started reading about these spiritual disciplines, yoga and Buddhism and Sufism, they told me that what I was doing had a right and wrong value. This is how this world is. There's always contrasting elements that create the world as we know it.

GT: By right and wrong, you mean like a moral, ethical code?

SR: Exaaactly. See. What you're doing is ethical. That music is right!

GT: Yes.

SR: All right.

GT: You, of course, have been known for your constant search, striving for self-improvement. I read in one interview that there's an ideal that you search for when you play. How would you describe that ideal?

SR: People say, what do you do when you improvise? You're a master improviser, and how do you do that, and what is jazz? I say, let me explain something to you: When I play and I improvise, I don't think, because music comes from the subconscious, someplace else. It's more than my stupid mind can think of. See, I'm just a human, so when I play my horn, I get into a state where the music plays me. I'm just standing up there and fingering my horn and blowing. See?

It's just like this day. Man, the day is just going, this day is moving, man, gettin' ready to go to tomorrow. It's subconscious, coming from a different place. And that's what jazz can allow you to do.

See, you learn what you have to do — the materials you wanna work with. You learn your harmony, learn your melody, all your rudiments that you need to play music. Then when you get up on the stage, you forget it. See? Then you let the spiritual take over. That's what I try to do, and I'm lucky because I do that automatically. So, I'm just trying to do more of it.

One way that I’m trying to be like Sonny is to let the spiritual take over during improvisational conversations such as this recent one on the “Hold My Drink” podcast with hosts Jennifer Richmond and David Bernstein. The hour-long discussion is titled “An Omni-American Ensemble.”