Jazz, Social Justice, and a White Boy from Texas

It happened on October 12, 1931. A sixteen-year-old white boy from Austin High School in Texas bought a ticket to see "Louis Armstrong, King of the Trumpet, and His Orchestra" at the Driskill Hotel. He knew nothing about jazz or this "King," he recalled many years later. Looking for fun, he attended because he thought girls would be at the dance.

What he ended up seeing and hearing astounded him.

"Steam-whistle power, lyric grace, alternated at will, even blended," he recalled. "Louis played mostly with his eyes closed; just before he closed them, they seemed to have ceased to look outward, to have turned inward, to the world out of which the music was to flow."

Armstrong was 31 years old. He had already changed the world of American music with his Hot Fives and Hot Sevens recordings. A few weeks after this concert, Armstrong would record versions of "Stardust" so stunning and vocally different from the original by Hoagy Carmichael that calling it avant-garde wouldn’t be a stretch.

"Pops" was at a peak of creative power.

The young man, named Charles, was a freshman at Austin High studying Greek classics. He had cordial relations with American Negroes, and liked most he knew, especially an elder named Buck Green, who was born and raised enslaved. When Charles was 10 years old, Mr. Green, then 75, taught him how to play harmonica. Yet whites in Austin, Texas, in line with Isabel Wilkerson’s brilliant analysis in Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, mainly saw Black folks as servants. Charles later realized that black professionals and intellectuals were present too, but those sorts of "colored" folk were invisible, beyond the pale of the caste system.

Nothing prepared Charles for the gift of Louis Armstrong: "He was the first genius I had ever seen...The moment of first being, and knowing oneself to be, in the presence of genius, is a solemn moment; it is perhaps the moment of final and indelible perception of man's utter transcendence of all else created. It is impossible to overstate the significance of a sixteen-year-old Southern boy's seeing genius, for the first time, in a black."

An Old Legal Lion Reflecting Back

Charles, by the time of these reflections in 1979, had already made his mark on history, and was an old lion reflecting on his life. He recalled that back in those Depression-era days some black folk "were honored and venerated, in that paradoxical white-Southern way" but genius, the "fine control over total power, all height and depth, forever and ever? It had simply never entered my mind, for confirming or denying in conjecture, that I would see this for the first time in a black man. You don't get over that."

That night, Charles was standing in the crowd with "a 'good old boy' from Austin High. We listened together for a long time. Then he turned to me, shook his head as if clearing it—as I'm sure he was—of an unacceptable though vague thought, and pronounced the judgment of the time and place: 'After all, he's nothing but a God damn nigger!'

The good old boy did not await, perhaps fearing [a] reply. He walked one way and I the other. Through many years now, I have felt that it was just then that I started walking toward the Brown case, where I belonged. I realized what it was that was being denied and rejected in the utterance I have quoted, and I realized, repeatedly and with growingly solid conviction through the next few years, that the rejection was inevitable, if the premises of my childhood world were to be seen as right, and that, for me, this must mean that those premises were wrong, because I could not and would not make the rejection. Every person of decency in the South of those days must have had some doubts about racism, and I had mine even then—perhaps more that most others. But Louis opened my eyes wide and put to me a choice. Blacks, the saying went, were 'all right in their place.' What was the 'place' of such a man, and of the people from which he sprang?

When Charles was brought face-to-face with an "other" who, in society, represented "inferior," yet turned out to be the total opposite of society's judgment—is not only "superior" but genius—he had a choice to make: do I go against the social norms about "race" in my Southern white upbringing? He eventually became, according to that upbringing, a traitor to his race and his class, what redneck "good old boys" would behind closed doors even today call an unrepentant "n-lover."

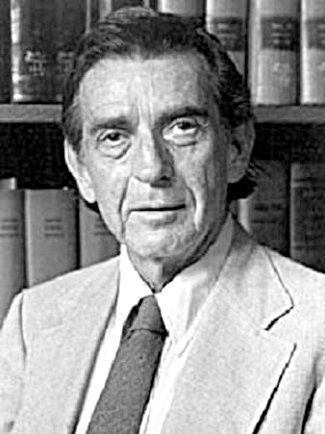

Professor and Social Justice Warrior Charles L. Black, Jr.

Charles L. Black, Jr. became a constitutional law professor who, for a half century, helped shape the legal minds of students at Columbia and Yale law schools. And, as recalled in his New York Times obituary on May 8, 2001, Charles Black helped "Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund Inc., and others, to write the legal brief for Linda Brown, a 10-year-old student in Topeka, Kan., whose historic case, Brown v. Board of Education, became the Supreme Court's definitive judgment on segregation in American education."

In the wake of the impeachment of Richard Nixon, Professor Black also wrote a definitive text:

A sterling example of moral courage, Charles L. Black, Jr's story above, which comes from an essay in the Yale Review titled "My World with Louis Armstrong," demonstrates the power of culture over race.

Transcending Race Through Culture

The cognitive dissonance Charles experienced over Louis Armstrong's glorious musical power was because of racial norms, his ultimate response to the experience, and subsequent reflections, was steeped in culture and morality, the same unity of aesthetics and ethics that, as I wrote in a recent previous post, freed me.

Charles L. Black Jr. freed himself from the constraints of "the judgment of the time and place" of the community in Texas in which he grew up by choosing to transcend them. That choice and his dedication to social justice later helped the country move beyond overt legal segregation in education via the Brown vs. Board of Education case.

He wasn't waiting for society to change, he was changing it by himself.

—Ralph Ellison

"There have been many—well, a good many—great artists in my time," wrote Black. "But it happened that the one who said the most to me—the most of gaiety, the most of sadness, the most of nervous excitement, the most of religion-in-art, the most of home, the most of that strange square-root-of-minus-one world of emotions without name—was and is Louis. The artist who has played this part in my life was black."

His reflections continue, encompassing the people from which Armstrong sprang and the culture he and they shared:

"In 1957, in the early days after the Brown case, when the South was still resisting, I wrote out and published my deepest thought on the nature of the agony as it presented itself:

I'm going to close by telling of a dream that has formed itself through the years as I, a Southern white by birth and training, have pondered my relations with the many Negroes of Southern origin that I have known, both in the North and at home.

I have noted again and again how often we laugh at the same things, how often we pronounce the same words the same way to the amusement of our hearers, judge character in the same frame of reference, mist up at the same kinds of music. I have exchanged 'good evening' with a Negro stranger on a New Haven street, and then realized (from the way he said the words) that he and I derived this universal small-town custom from the same culture...

These and thousands of other such things have brought me to see the whole caste system of the South, the whole complex net of its senseless cruelties and cripplings, as no mere accidental grotesquerie of history, but rather as that most hideous of errors, that prima materia of tragedy, the failure to recognize kinship...My dream is simply that sight will one day clear and that each of the participants will recognize each other.

The question to you, dear reader, is whether or not you will, as did Charles Black, choose culture over race, and recognize each other’s common human inheritance and kinship?