I Almost Became a Racist. Then, Jazz Saved Me

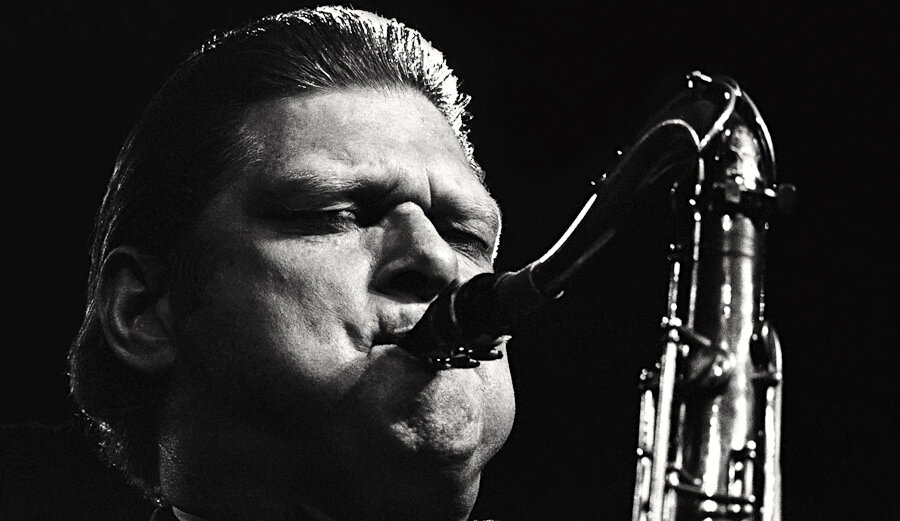

Phil Woods

It’s true: jazz saved me from becoming a racist.

Back in the early to mid-1980s, while attending Hamilton College in central New York, I learned details about the transatlantic slave trade that sickened and angered me. I read about the history of the abolitionist movement in the 1800s, and the civil rights movements of last century, as well as the apartheid-like Jim Crow system that arose in between those movements. "Jim Crow," particularly in the U.S. South, maintained the economic, social and institutional power of whites over blacks and others with darker pigmentation, based on the legal doctrine "separate but equal" and a damnable myth: white supremacy.

In 1983, as leader of the Academic Chamber of the Student Assembly at Hamilton, I even came across documents by the Curriculum Committee that condescended away the lack of an African Studies concentration—mind you, they had Asian, Latin American and Middle East Studies at the time—by “reasoning” that Africans were not heir to the "great traditions."

Yet it was the great tradition of jazz that rendered me immune to leaping from anger to hatred of white people. My family upbringing as a Christian gave me a moral grounding too, yet it was my adoration, as a teen in Staten Island, NY, of the jazz styles of so-called "white" saxophonists such as Paul Desmond, Zoot Sims, Phil Woods, and my private sax teacher Caesar DiMauro, that aligned my heart with my soul.

Ethics and the Aesthetic

Among other things, moral precepts and a belief system are guides for behavior and one's conscience; the music, rather, gets into your body-mind/mind-body, stirs your emotions, and resonates with your memory. The undeniable truth of the beauty of jazz elevated my consciousness to a higher octave of cultural good.

I didn't segment who I listened to according to race, so as a 15-year old beginner alto saxophonist I enjoyed a plethora of alto saxophonists across time, from Johnny Hodges and Benny Carter, Charlie Parker and James Moody, Lee Konitz and Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson, Cannonball Adderley and Louis Jordan, Frank Strozier and Sonny Stitt to Hank Crawford, Sadao Watanabe, Charles McPherson, David Sanborn, and Grover Washington Jr.

And while attending Tottenville High School, where I played in the concert, symphonic, and stage bands, I also took sax lessons with a local legend, Caesar DiMauro. He performed European classical music on oboe and alto sax; he played jazz saxophone on alto and tenor. Caeser was a gentle soul who loved to make and drink wine. He'd play with other local legends such as guitarist Chuck Wayne and trumpeters Don Joseph and Mike Morreale, who taught music occasionally at Tottenville.

Caeser DiMauro

Memories of Caesar

Caeser loved Zoot Sims' playing. His friends loved to tell the tale of the time DiMauro headed to hear Sims at the Blue Note and sat in. That night, reportedly, Sims liked DiMauro's riff-style too, and shouted, "Go, Caesar, go!" DiMauro's expressive approach on tenor was derived from Prez, Lester Young, but toward the end of his life his muscularity reminded me of Hawk, Coleman Hawkins.

I'd meet him at his woodshed on the South Shore of Staten Island, off Arthur Kill Road, and he'd take me through the fundamentals. He even taught me the art of trimming off tiny amounts of excess wood from the edges of Rico or Vandoren saxophone reeds until you could see a smooth bell curve shape when you held the reed up to the light. We'd later meet at the Jewish Community Center on Victory Boulevard and Bay Street to play etudes from jazz duet collections and passages from the Universal Method for Saxophone (Carl Fischer, 1908), by Paul DeVille.

I'll never forget the time he told me: "Greg, you learn all of the scales, chords, arpeggios, and patterns, but after you have them down, and you begin to improvise, let that stuff go and just play."

Caesar playing at The Dock of the Bay in Staten Island

Should I Bite the Apple of Hate?

In college, however, my own understanding of race relations and the history of my cultural kinfolk—Black Americans—heightened and deepened beyond the grainy black and white footage of Bull Connor ordering fire hoses to be used on Negroes in Selma, Alabama, beyond Martin Luther King's "I Have a Dream Speech," beyond the annual remembrances of Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and Sojourner Truth during Black History Month in February, and even beyond Alex Haley's mini-series Roots (1977), which I watched with anger and incredulity as an adolescent while going to junior high.

If the devil is in the details, my increasing awareness of the extent of the treachery, cruelty and greed of those who perpetuated human enslavement and social, economic, and political oppression tempted me to accept the Nation of Islam's assertion that white people were really devils! Plus, while attending Columbia University for the first semester of my senior year in 1984, where I took a literature class with Amiri Baraka, I saw up close the movement demanding corporations to divest from investments in apartheid South Africa. The injustice of a white minority dominating and brutalizing the black majority there incensed me also, and I became more politicized.

Zoot Sims

But, lo and behold, Caesar DiMauro (Italian-American), Zoot Sims (Midwestern and Southern roots), Paul Desmond (German and Irish), and Phil Woods (Irish and French) had too strong a hold on my ears and feelings for me to accept such a racist claim as white folks, as a group of people, being devils. By the way, their sort of mixed lineage and heritage is what I'd later discover writer Albert Murray meant by his phrase "Omni-American." Wouldn't you agree that the word "white" in fact "whites out" their cultural and ethnic background?

A Faustian bargain, indeed.

Listening to Sims and Desmond led me back to Prez too—though Sims had some Hawk and Ben Webster in his swagger—but I liked them for their own individual qualities. Sims' plangent passion and poised yet explosive swing on If I'm Lucky: Zoot Sims Meets Jimmy Rowles (Pablo, 1977) is one of the recordings that deepened my sonic romance, and the wry dry martini quality of Desmond's gentle tone on his dates with Dave Brubeck and Gerry Mulligan seeped into my young foolish heart.

Paul Desmond

Yet when I was 17, it was Phil Woods' combination of technical mastery in service of emotional expression that blew me away. He joined a pantheon of artists—Bird, John Coltrane, Sarah Vaughan, Cannonball, Miles Davis and Clifford Brown—I immersed myself in, each of whom baptized me in the improvisational fires of musical greatness.

Even more than his sideman work with Thelonious Monk, Clark Terry, Billy Joel, and Steely Dan, I remember Woods' early records that I would borrow, over and over, from the New York Public Library—Altology (Prestige, 1957), Sugan (Prestige, 1957) Phil & Quill With Prestige (RCA, 1957)—as well as his transcendent performance of the title track to Quincy Jones' The Quintessence (Impulse!, 1962), and his awe-inspiring sax prowess on Live From the Showboat (RCA, 1976). Like Cannonball, Woods synthesized Benny Carter, Johnny Hodges and Bird in his own unique way, creating a sound and style all his own.

Cannonball Adderley and Phil Woods

In 1979 or 1980, while still in high school, I snuck into a performance Woods gave at a high-class hotel in Manhattan to hear his mastery live and direct. I remember admiring the way he seemed to barely move his fingers over the keys of his glistening Selmer sax while producing such incredible lines, some richly melodic and lyrical, others flaming with the exciting velocity of bebop.

Me & Phil after his amazing set

I wore out the vinyl LP grooves of I Remember (DCC, 1978), and Woods' original compositions and arrangements in tribute to Cannonball, Desmond, Oscar Pettiford, Oliver Nelson, Bird, Willie Rodriguez, Willie Dennis and Gary McFarland became part of my high school soundtrack. His tribute to Desmond, "Paul," cast such a spell that I bought the sheet music of Woods' improvisation—to try to learn to play it, yes; but more so to read the music along with the record, as my mouth lay agape in astonishment.

My teacher DiMauro, Sims, Desmond and Woods all became a part of my soul, so my love of them transferred to my moral center and conscience, which ultimately made me recoil from the temptation of racism during college. The beauty of their jazz performances and the wisdom of Caeser’s instruction, in an art form created and innovated by my cultural ancestors, made them, for me, aesthetic heroes whose "race," in relation to appreciating the music, was an insignificant consideration on one level, but significant enough, ironically, to help me avoid the hellhole of hatred and racism myself.

To hear and feel for yourself Phil Wood’s mastery with strings and rhythm section on “I’ll Remember April” and “Paul,” just click below.

PS: I’ve long since forgiven my alma mater, as should be clear by my recent interview with Hamilton College’s President Wippman.