In Honor of Greg Tate

Honoring Greg Tate, a singular sui generis stylist of Afro-English-language criticism calibrated through an all-embracing Black sensibility, is bittersweet. Unlike the loss of Stanley Crouch, Tate’s colleague at the Village Voice, which I knew was coming due to a long illness, Tate’s death last week at the age of 64 was a total shock.

We last spoke on October 29, discussing music, a recent performance of his Burnt Sugar band in Connecticut, his commencement address this past May at the Yale School of Art, and the project we were working on together.

Similar to the many critics and academics whose flood of appreciation and remembrances of the man I called “my fellow GT,” as a writer and critic of music I was influenced by his example, by his freestyling versifyin’, by his range of reference and depth of insight, by his infinite love of the souls and art of Black folk.

As he’d boom-de-bap converse about the verities and limits of Afro-Futurism to Afro-Pessimism, he’d have one foot in modernist and post-modernist canons of literature, visual art, film, music and criticism, and the other in the streets of Harlem to Greenwich Village to SoCal and Paris, tracking and chronicling what’s hattenin’ with the soulful verve the vernacular kulcha deserved.

But since my fellow GT was a friend, my feelings for him aren’t just professional. I loved Greg Tate as a person and as a man.

I first met him in Harlem in the late 1990s, having moved to 153rd Street and St. Nicholas Avenue. He lived on Edgecombe Avenue several blocks up the street. Before we ever spoke, I recall him attending meetings of the Jazz Study Group at Columbia University, which became the Center of Jazz Studies. Once we spoke, his cool ease, warmth and poise, and soulful humor were added to my impressions of him on the page.

But we nurtured what had been a casual acquaintance in the past seven years after agreeing to a public debate. Greg was inspired to become a writer in part through the influence and example of Amiri Baraka; I, on the other hand, was more inspired by Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray as filtered through the writing of Stanley Crouch. On Facebook, circa 2014, Greg and I were engaging in some repartee and call-and-response about the virtues of Baraka in comparison and contrast to Ellison.

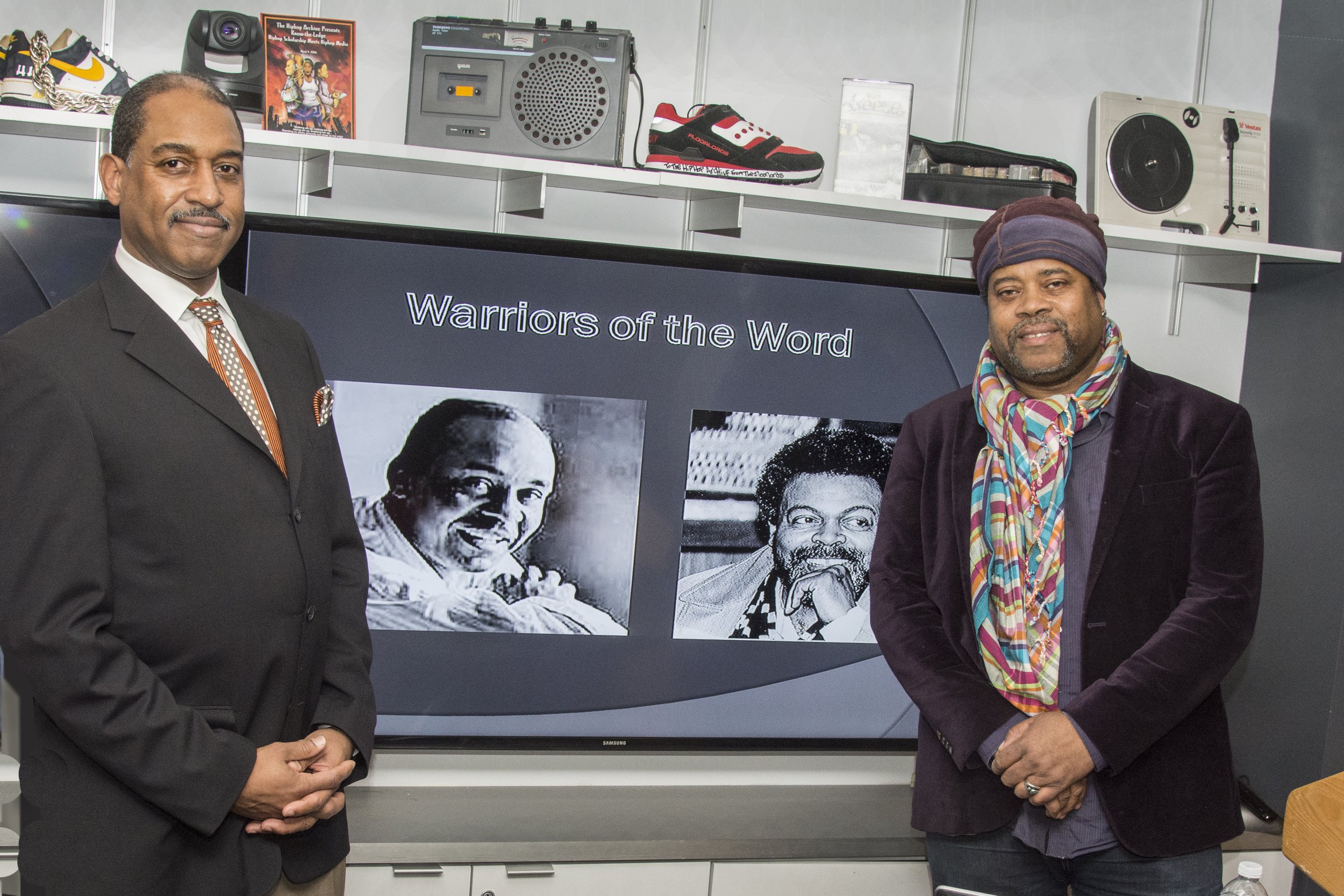

So I called Greg and suggested that we take such jewels beyond the wasteland of Facebook and plan a public debate. We decided to write a series of letters to one another, him representing Baraka and Blues People and me the position of Ellison critiquing Baraka and his first nonfiction book. My alma mater, Hamilton College, was the first place we engaged one another; then, with the imprimatur of Henry Louis “Skip” Gates, we shared our series of letters at the Hip Hop Archives at Harvard in 2016.

At Hamilton College, after our Ellison-Baraka debate. Philosophy professor Todd Franklin (left), Greg Tate (right)

After our debate at Harvard. Marcyliena Morgan, professor and executive director of The Hip Hop Archive and Research Institute, is in the middle

What follows are excerpts of the first of three letters we each wrote for our debate, in which we—as Greg described it—“reanimated” a debate that could have happened between Ellison and Baraka but never did:

Dear Greg Tate:

Thanks for agreeing to this exchange, a pursuit of the lessons we can learn from the Ralph Ellison-Amiri Baraka nexus on the blues, jazz, culture, politics, race, class, American identity, and American destiny. At least that’s how I see our conversation in letters, which is somewhat a show down-throw down, since I’m taking Ellison’s side, and you Baraka’s.

To paraphrase Frederick Douglass: “No struggle, no progress.” So let’s deal with the struggle as portrayed in the life and works of these two gentleman, and determine how we have progressed—or not—in the wake of their words and actions in the world.

Straight-up: Ellison kicked Baraka’s ass in that February 1964 review of Baraka’s Blues People, and did it in dashing, signifyin’ fashion. The blues, as music and an aesthetic, as a homegrown existential world-view and philosophical anthropology, had been important to Ellison for quite some time. In 1945, when your man Baraka was just 11 years old and still had his birth name—Leroi Jones—Ellison, then 32, wrote what’s become a definitive description of the blues:

The blues is an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in one’s aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain, and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near comic lyricism. As a form, the blues is an autobiographical chronicle of personal catastrophe expressed lyrically.

That quote, from the essay titled “Richard Wright’s Blues,” could be the foundation for an entire course at Harvard!

And now we know that Ellison and his long-time main man, Albert Murray, had deep discussions about the cultural power and meaning of the blues and jazz all through the late ‘40s onward. Their letter exchanges through the 1950s, published in 2000 as Trading Twelves: The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray, and their fiction and nonfiction overall, clearly display their cosmopolitan ease with the Western tradition of literature, their global view of myth, ritual and history across the ages, and how these relate to what Ellison called the Negro idiom and Murray termed the blues idiom.

Ellison, the man whose 1952 novel Invisible Man is, as you well know, a world-class 20th century polyphonic classic, accepted the ancestral and intellectual imperative to define black American culture AND American identity. So he couldn’t let your man Jones get away with theorizing the blues, as he put it, “straining for a note of militancy,” with an “introductory mood of scholarly analysis” that, unfortunately, “frequently shatters into a dissonance of accusation.” Ellison thought that Jones’s Blues People was too burdened by sociology, and that, in musical terms, his pitch was at times too sharp, at others flat.

“One would get the impression that there was a rigid correlation between color, education, income and the Negro’s preference in music,” Ellison wrote. Then he makes a signature Ellisonian move, whereby the thesis of the singular, and the antithesis of the complex synthesize into the exceptional . . . .

Greg Tate:

Now G, nobody loves Ralph E’s all-seeing all-knowing ratiocinating novelist’s brain like moi—Invisible Man being in this reporter’s humble take, the most complex and variegated portrayal of archetypal African masculinities at war in the muck of American race politics that our serious literature has yet produced.

Kendrick Lamar’s Good Kid, M.A.A.D City and To Pimp a Butterfly may already be being studied as modern, sonic fictions that speak to Ellison’s ongoing existentialist omni-presence in our most contemporary of musical paraliteratures.

But about Ellison’s take on Blues People, I agree with Larry Neal, who said Ellison’s review of Blues People basically just sounded like notes towards the blues book Ellison should have written himself and never did.

Could be Ellison’s podna in crime Albert Murray performed that duty for their intellectual tandem when he wrote his expository classics The Hero and the Blues and Stomping the Blues? I’ll grant that far as it goes.

Because let’s be real: given Ellison’s own eloquent dropping of blues-(k)no(w)logy in that legendary descriptive passage you quoted, Ralph E calling out Amiri B for Black on blues theorizing seems a reprise of some epic name-calling between that kettle and that pot.

It’s also worth noting that the classic and oddly Oedipal Battle Royale quality of Ellison The Emperor going after Baraka The Younger’s first blues child-baby. All loud out there on the world stage and just as Baraka’s own white-hot star was rising in the New York literary and theatre world.

For his part, Baraka never said much else about Ellison except what he dropped in his 1965 essay “LeRoi Jones Talking,” where he considered Ellison’s fate in American Letters as a cautionary tale—that of a Black man so isolated and enshrined in the lily-white academy and unable to generate more significant writing—a model to Baraka of exactly the kind of caged bird he didn’t want to end up being.

All that aside, though: let’s deal with specifics re: Ellison’s criticisms of Blues People. In a nutshell, I’d just say that in that review we certainly find one of the more wrathful misreadings of one brilliant writer by another ever put to pen.

First off, if Ellison really had an issue with class analysis and even Marxist class condemnation of the bourgeoisie as a feature of Black cultural observation, he would never have given us the gut-wrenching, class-drenched contrast between his Bledsoe and Trueblood characters in Invisible Man.

Or never depicted his nameless, hapless and deeply alienated Joe College protagonist’s blues as those of one seriously miseducated, class-mobility distressed Negro—one revealed in his pilgrim’s awkward progress as frighteningly estranged from working class 1930s and ‘40s hard scuffle, hipster-graced Harlem.

So let’s take a minute here and talk about what’s really going on in Blues People as a sui generis work of self-confessedly theoretical speculations on the history of Black Music in America from slavery to the then-now of 1964, the YesterNow, ydig—per Miles Davis’ coinage . . . .

Now that his spirit is among the ancestors, I intend to publish the entire exchange in Greg Tate’s honor. Ashe.