Evolutionary Biologist Brandon Ogbunu on COVID-19

Dr. C. Brandon Ogbunu

Introduction

Last year, I met evolutionary systems biologist Brandon Ogbunu through his colleague at Brown University, Stephon Alexander, author of The Jazz of Physics and a personal friend. When I explained my exploratory inquiry into the art and science of improvisation for a class I led at Jazz at Lincoln Center, he was intrigued. When I said that I’d like to him to join Stephon for presentations aligning their knowledge of physics and biology with aspects of jazz, he immediately said yes.

Describing his own work, Dr. Ogbunu says: “I am broadly interested in evolutionary complex systems, often in the context of disease. My research aims to disentangle the complex interactions underlying disease phenomena across scales, ranging from the higher-order epistasis operating in drug resistance at the molecular level, to the many forces that craft epidemics at the population level.”

After obtaining an undergraduate degree at Howard University, he went on to earn a PhD at Yale, followed by post-doctoral work at Harvard. After several years of research and teaching at Brown, he will join the faculty of Yale this fall.

Thanks for taking the time to speak with us, Professor Ogbunu. Please share with our readers how your work intersects with research on COVID-19.

My research investigates the many ways that viruses like SARS-CoV-2 (the cause of COVID-19) spread. For example, we know that a lot of viruses can get from host to host by direct contact between hosts. I’m interested in the specific tricks that viruses use to get from host to host, and specifically, the idea that viruses can spread from person to person by living in the environment.

We are interested in understanding how this happens, and how it contributes to different patterns of COVID-19 in different settings.

For example: we know that SARS-CoV2-2 lives for different amounts of time on different surfaces, like plastic and copper. If we know this, then we can examine how much being surrounded by these types of surfaces can influence how fast the disease is spreading.

Has your research uncovered how long the virus lives on such surfaces?

Survival differs by surface. On some surfaces, like copper, the virus doesn’t live especially long, less than a couple of hours. On plastic, however, the virus can survive for over 6 hours. Our lab did not conduct the original laboratory research, but we investigated how differences in surface survival can influence how intense the epidemic can be.

How was this research conducted?

Our group used mathematical models, based on data from the actual COVID-19 outbreak, to make estimations on how different surfaces would facilitate outbreaks of different intensity.

You mention “our group.” Tell us about the composition of your research team.

My research team comprises a range of individuals of different stages, areas of expertise. These include graduate students, research associates, and other professors that I collaborate with.

They have a breadth of skills that are important for understanding COVID-19. Some are statisticians that are good at understanding the analysis of real-world COVID-19 data. Others are mathematicians who are skilled at building and understanding mathematical models. Others are microbial ecologists who understand how microorganisms live and function.

The key is in how we are able to speak to each other.

How would you describe how your team speaks to each other?

We generally utilize an “inverted triangle” approach: We start with the big picture and work our way down to specific topics or areas. We do this almost every meeting, to ensure that we are all on the same page about the basic questions.

Science as Creative and Collaborative

In your article, “Don’t Be Fooled by Covid-19 Carpetbaggers,” in which you gave sensible guidelines on ways to evaluate “who to take seriously and who to ignore” regarding Covid-19 expertise and opinion, you wrote, “Science works best as a creative, collaborative enterprise.” This aligns with our point of view on jazz as a leadership and team synergy model. Can you elaborate on that statement?

Yes, the notion that science is a creative and collaborative enterprise is obvious to some scientists, but not to others. Because I have some artistic leanings (as a writer), I always see the process of science as being truly creative.

It is fundamentally based on developing original ideas, that come to me as moments of inspiration.

And like other creative endeavors, execution often involves cultivating said ideas individually, the eventual communication of ideas with others, and then the execution with a team of individuals. Successful science occurs when all of these steps are achieved.

I try to be thoughtful about all aspects of the process.

Screen Shot of Dr. Ogbunu’s April 2020 article in Wired magazine

I understand why the hunt for a vaccine to counter COVID-19 is necessary. But I wonder why, in the meantime, health authorities don't generally suggest ways to improve your immune system, such as regular intake of vitamins C, A, and D. Can you explain why this might be the case?

While vitamins and minerals (and a healthy diet), and, more generally, being in good health are good for many body functions (including the immune system), I don’t think these would work as a concrete recommendation for addressing a widespread disease like COVID-19.

Certainly, behaviors that promote poor health, like smoking, should be avoided. But our past history in public health, having dealt with epidemics, has demonstrated that the most effective way to address a highly contagious viral disease is through a vaccine. So I do think the research into one is a good idea.

Additionally, I’m actually encouraged by the possibility that there may be antiviral drugs that we can use to address this virus. Several are being tested.

One of our very first posts after the declaration of this novel strain of the coronavirus as a pandemic involved the mental health impact of social distancing. What do you think social distancing has done with respect to creativity?

Great question. At one level, anything that is bad for people is going to bad for creativity. That is, if people are unemployed, feeling constrained, or stressed out, then I could imagine that it would be bad for the creative process.

Creativity is like many functions, and it requires certain needs to be met in order to operate at the maximum level.

On the other hand, there are other aspects of the social distancing phenomenon that have been good for my own productivity. I think that this era has forced people to sit and reflect on many areas of their lives. Their privileges, their loved ones. And deep thinking, regardless of what drives it, can be good for the creative process.

I’ve found myself having longer streams-of-consciousness moments, and I’ve accessed areas of myself that have been generative. I also think social distancing has forced me to re-think the process through which I establish an idea, record it and develop it. So I’ve been thinking more carefully about the time of day that I write best, for example, which has helped my creativity and productivity.

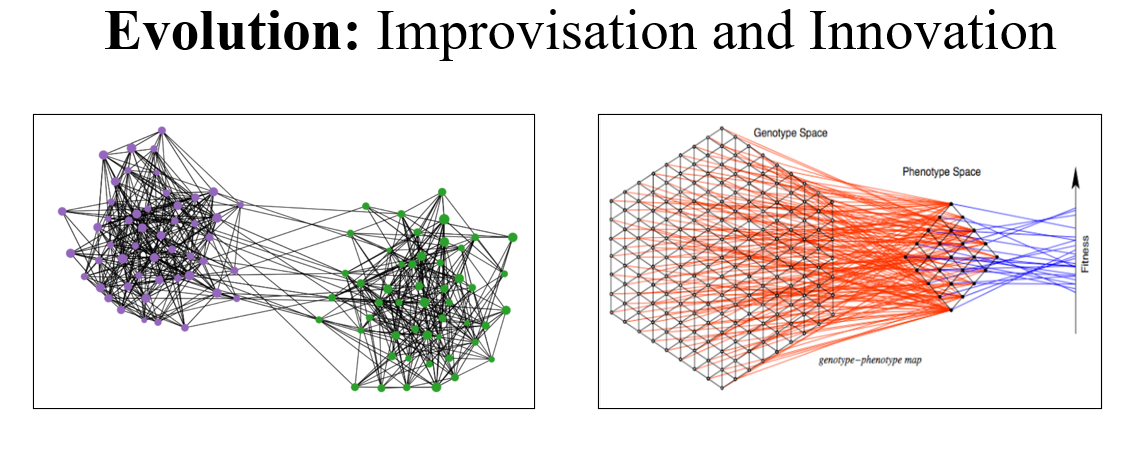

Opening Slide from Professor Ogbunu’s presentation at JALC

When you graciously consented to making a presentation at Jazz at Lincoln Center in 2019 for an adult ed class session I titled “Does Life and the Universe Improvise?” you related the very evolution of life to processes akin to jazz. Could you summarize the relationship as you see it?

Well, one famous computational biologist named Eugene Koonin refers to evolution by natural selection as “the logic of chance.” That is, evolution is a random process at one level, but through it, it can move logically and build sophisticated objects and algorithms, such as life on earth.

I see several similarities to processes like improvisational jazz. It can appear at one level like the individual instruments and sounds are independent and unconnected. But the musicians and sounds interact in these subtle but profound ways to create these sound tapestries, these murals of music that are elegant.

Are you saying that the emergence of life itself is like an elegant improvisation?

I think that there are similarities. There are, of course, major differences as well –- improvisation is still an action orchestrated by an individual musician. the “improvisation” of life doesn’t have such an actor.

Inspiration and the Creative Process

As a scientist who also engages in writing for the general public as a creative endeavor, would you explain why you take the time to do this when your research and teaching duties at an Ivy League institution take up more than enough of your time?

I find all of my work—my formal scientific work, my teaching, all of my writing (both non-fiction and fiction) to be part of one creative process. Though the works themselves are different, they all involve inspiration.

Consequently, creativity in one realm often feeds other realms. That is, I can honestly say that I have produced real scientific work that arose from when I read an interesting piece of science fiction. Even the fictional world can influence my scientific reasoning.

Relatedly, I’m currently writing a science-fiction story that was inspired by some of my COVID-19 research. This is useful because it keeps my ideas fresh. I don’t get “writers block” very often, because my mind shifts to other realms and doesn’t remain fixated on any one area.

Strangely, my process helps me to be more efficient, to get more things done. There are challenges, of course, and I’m always looking to improve my process, be more efficient, but I’ve had some success with my methods.

Public Intellectual?

Your writing for a general audience, not only for your scientific peers, sounds to me similar to what used to be called “public intellectual” work. It’s also a leadership stance as a scientist. Who are examples within the scientific community, past and/or present, who you admire and why?

Well, if I am a public intellectual, it is not because I try to be. I enjoy engaging broad audiences with my ideas, but truly believe that I can have the most impact if I’m creating great ideas that are impactful and important in my field. So I try to generate scientific ideas that are impactful before I do ones that are popular.

That said, I never shy away from public discourse. And I have been inspired by many scientists and thinkers. Evolutionary biologists who wrote popular books like Stephen Jay Gould were really important for my development. Others include neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky. I enjoy the writing of historian Jill Lepore, scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr, and many others.

But all of the people I just mentioned are pretty famous. Some of my favorite public intellectuals of today are newer to the scene, like Carl Bergstrom and Pleuni Pennings.

I am inspired by all of them for their contributions to making ideas more accessible. And there is a consistent theme: all are top flight experts at something, while engaging the public. It’s a challenge, but is a rewarding aspect of this profession.