Work: A Meditative, Spiritual Journey

I believe that my work will heal my personality, that it will allow me to know more of who I am and experience more emotions. So, then I can understand more of what my motives are in life. I look at my work as a meditation, as a spiritual journey. It’s an investigation for me.

—Giancarlo Esposito

Greg and I watched the entire eight episodes of the new Netflix show “Kaleidoscope” this week—it was that good. A captivating caper, the episodes are not numbered, but titled different colors and can be watched in any order, which was fun.

In a recent New York Times article, a cast member called lead actor Giancarlo Esposito a “really lovely team leader,” while another said that he always tried to give his best energy to create a good atmosphere. Esposito’s quote reveals not only a deep commitment to his craft, but also an appreciation of how his craft reveals the depths of who he is as a person—as he says, “the good, the bad, and the ugly.”

Work as healing—a transformative perspective.

Work as a spiritual journey—a quest for understanding.

Esposito’s words, intimately introspective, provide a nuanced approach to work, and brought to mind a post I wrote a couple of years ago about how artists provide opportunities for us to move through life transformations.

Artists As Transformative Leaders

Art is the revelation of our soul’s beauty and the balm that heals its wounds.

—Jewel Kinch-Thomas

Sandford Biggers, “lotus”

It’s been beautiful to open the weekend New York Times art section and find story after story regaling the extraordinary talent of African-American artists who continue to shape the cultural landscape of these United States. So when I recently read an article about sculptor and quilter Sanford Biggers, it reinforced and reaffirmed just how powerful the arts are to open spaces for connection, reflection, and deeper understanding.

Art-making and art-viewing allows us to express and process our experiences of the world around us. That experience can be a source of comfort and promote kindness and love—as we’ve seen during the stress of COVID-19.

From the individual expression of the artist, the artwork transmutes into a communal, universal experience as the narrative and sensations take hold, boring into the depths of our soul.

Art helps us process trauma and articulate difficult feelings. It makes social injustice visible, reflecting our past and current worldviews, while sending a powerful message to the public. In moments of strife and chaos, when we need to make sense of the tumultuousness of life, artists gift us the pathways to dialogue, and yes, healing.

Sanford Biggers, “BAM (for Michael)”

Interdisciplinary artist, Biggers challenges viewers with popular imagery juxtaposed against that which is appalling. “Lotus,” above, is a blossom etched on glass with a mandala motif. Upon closer examination, the petals illustrate the cargo holds of several 18th Century slave ships, lined with the bodies of the enslaved.

In response to ongoing police brutality against Black Americans, Biggers’ BAM (for Michael, for Philando, for Sandra) series is composed of wooden African statues, dipped in wax, ballistically ‘resculpted’ at a shooting range, and then recast in bronze.

Biggers says: “The BAM series, I think, are really beautiful but really horrific. And that is the sort of tension that I like my work to have, something very compelling and seductive but at the same time something very hard and almost disturbing…If you as a viewer are willing to go through that experience, there is a resolve and there is a sense of transcendence that I'm aiming for.”

Leading Through Creativity

If leaders inspire, envision possibilities, and create space for us to evolve, then artists lead by virtue of the art treasures they gift to us. By making aesthetic statements, African-American artists create value for a people who have been ignored or dismissed for centuries. I appreciate the lens that allows for such recognition, bringing healing to the disenfranchised and a new perspective to those who’ve failed to recognize that value. Beyonce’s “Black is King,” an ode to “the breadth and beauty of black ancestry,” is such a statement, exquisitely told.

art tells our stories . . .

showing us who we are

art displays the reality of our moment . . .

helping us find our way through to sense-making

art breathes life into things shunned and relegated to the shadows . . .

illuminating passageways to transparency and appreciation

In a time of uncertainty about what to say, how to say it, how to behave, and how to build better relations, art provides a means to honor the history, untangle the falsehoods and stereotypes, and start from a place of authenticity and truth.

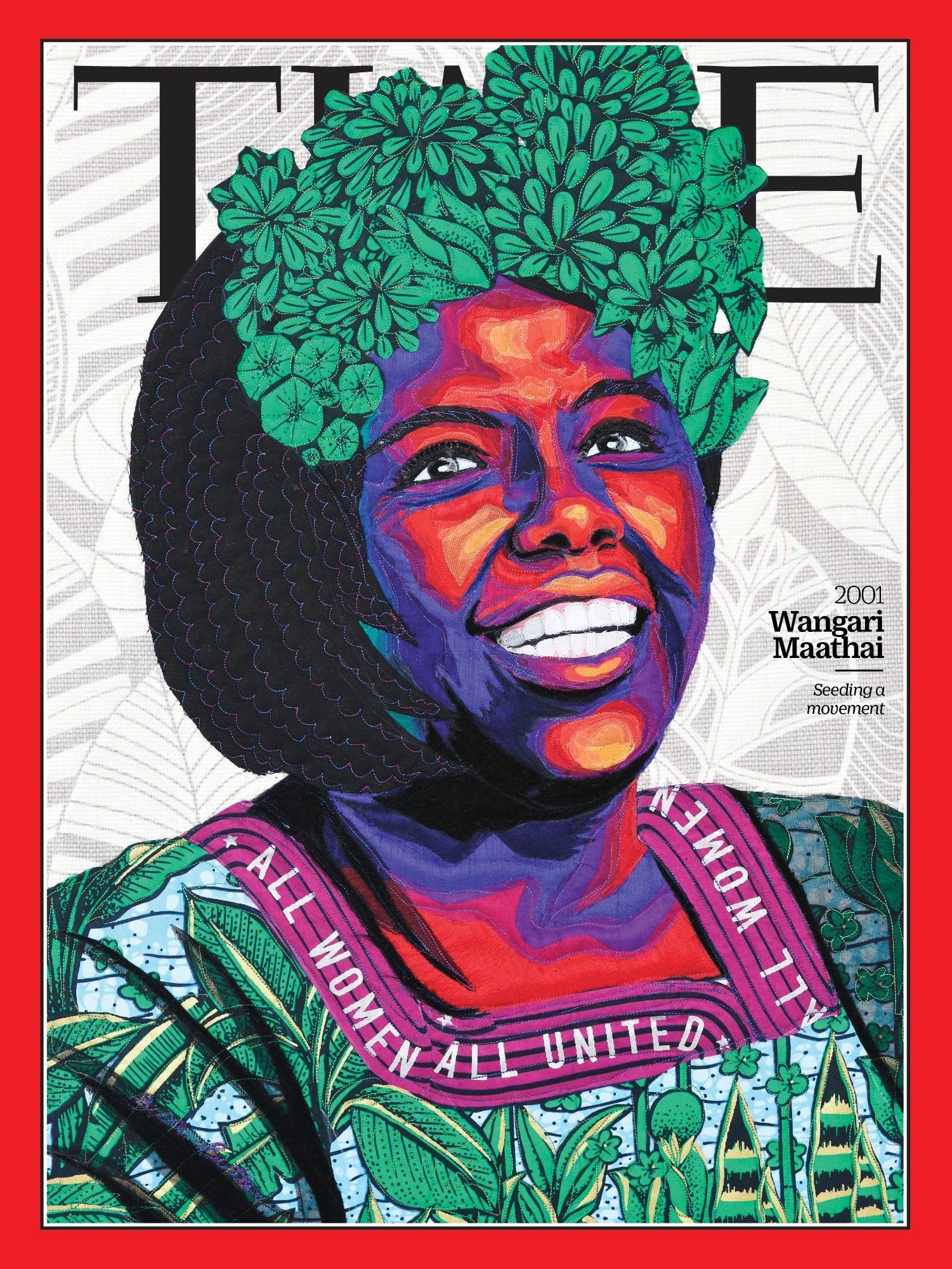

Quilts hold a very special place in African-American culture, paying homage to ancestry and family. Quilter Bisa Butler was a finalist for the Museum of Arts and Design’s prestigious Burke Prize in 2019. Her quilted portrait of Wangar Maathai, the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize for her environmental and women’s rights activism, was selected to be a Time magazine cover for this year’s issue honoring 100 women. Bisa Butler sees herself as a storyteller.

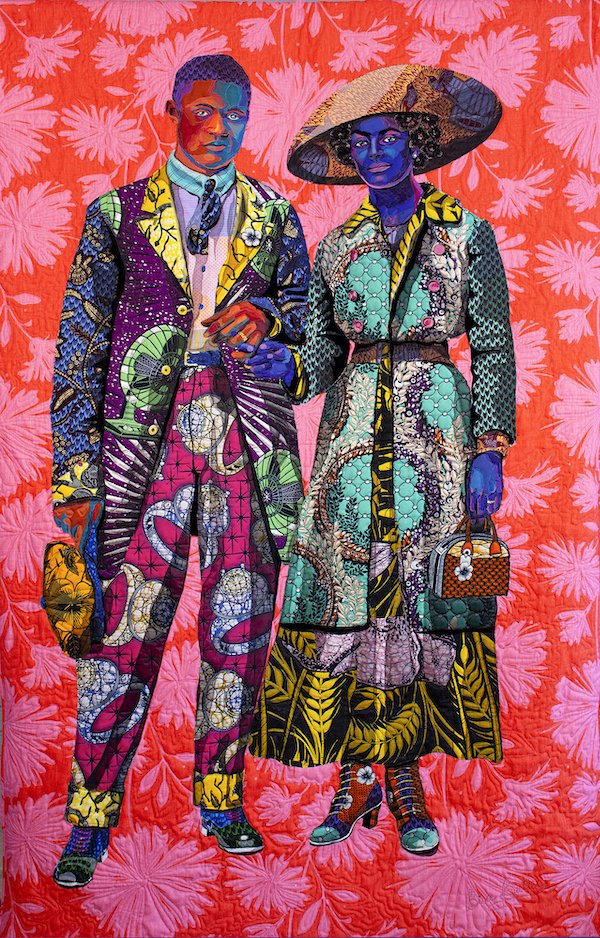

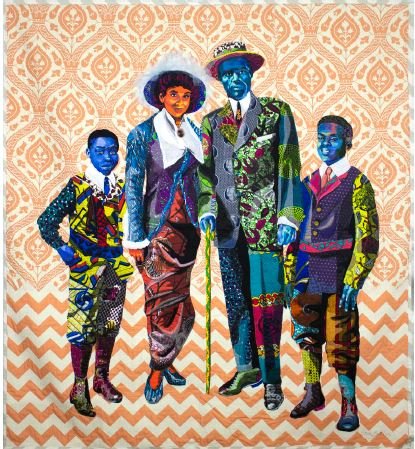

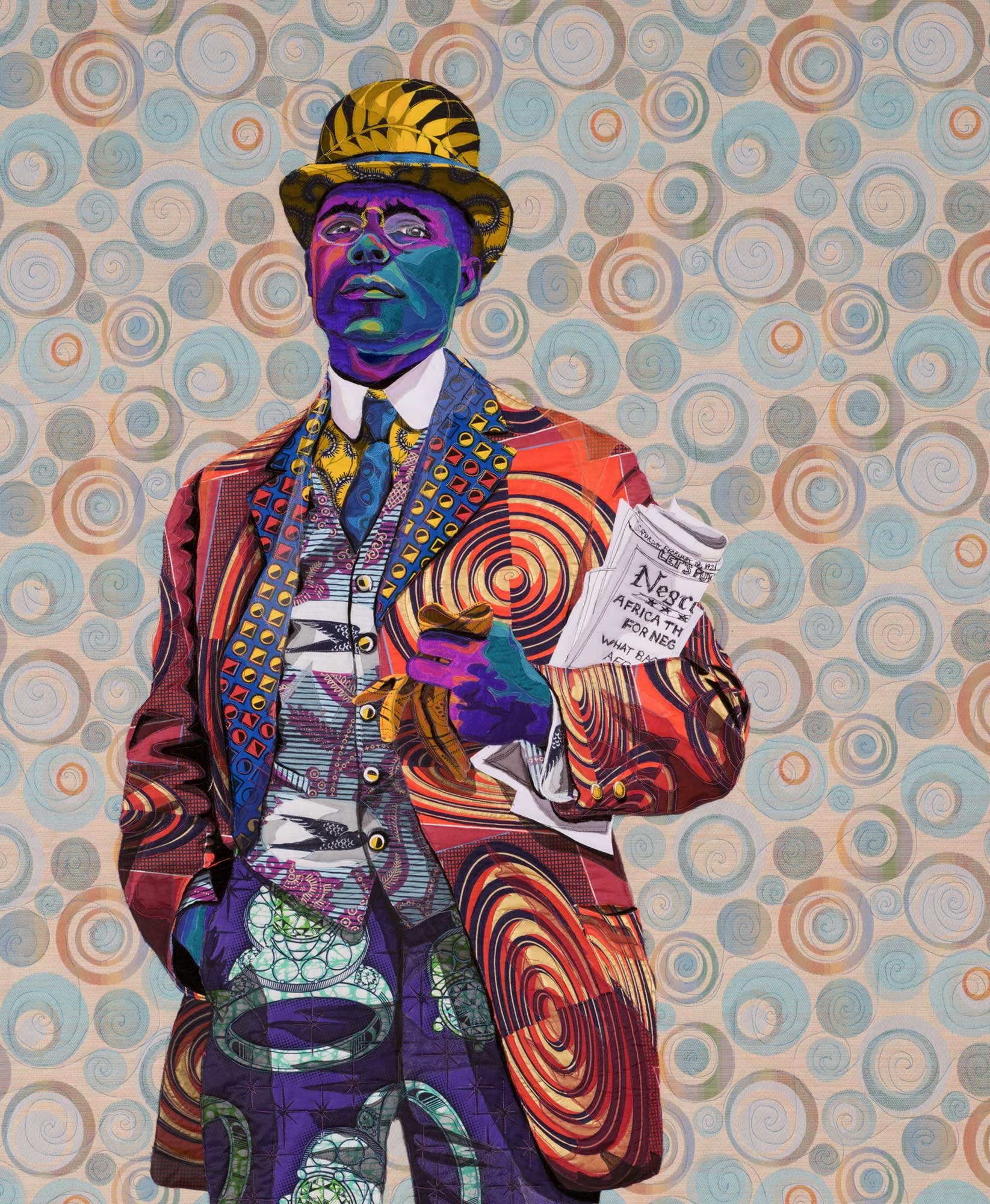

"In my work, I am telling the story—this African American side—of the American life," Butler says. "History is the story of men and women, but the narrative is controlled by those who hold the pen."

Butler feels obliged to “tell the story to the masses” — the unknown story of everyday people, with vibrancy and dignity, to correct the misinformation she believes is ever present. She is fascinated by these people because she knows them—her parents, aunts, and grandmothers.

To reinforce the narrative of her portraits, Butler uses specific African prints. “A fabric that has images of a grade school primer on it is called ‘ABCD’ and men and woman wear it to symbolize that they are literate and value education. A fabric called ‘Jumping Horse’ is used to symbolize the phrase ‘I Run Faster Than My Enemies,’ or in other words, the wearer triumphs over adversaries.” Butler says she has never been drawn to artwork that “provokes sympathy and makes you feel sorry for the subject.”

I’ve always been a big proponent of holding talk-backs between the artist and the audience for most events I’ve produced, particularly when the artwork was focused on an issue of injustice. The opportunity to synthesize the experience always activated energetic and meaningful civic discourse. The communication sometimes sparked heated debate, brought out differences in perspective, but always opened a space to reveal and excise those haunting shadows.

Bisa Butler creates live-size portraits because she wants the viewer looking eye-to-eye with her subjects. There’s no better position from which to begin a dialogue.