The Color of Defiance

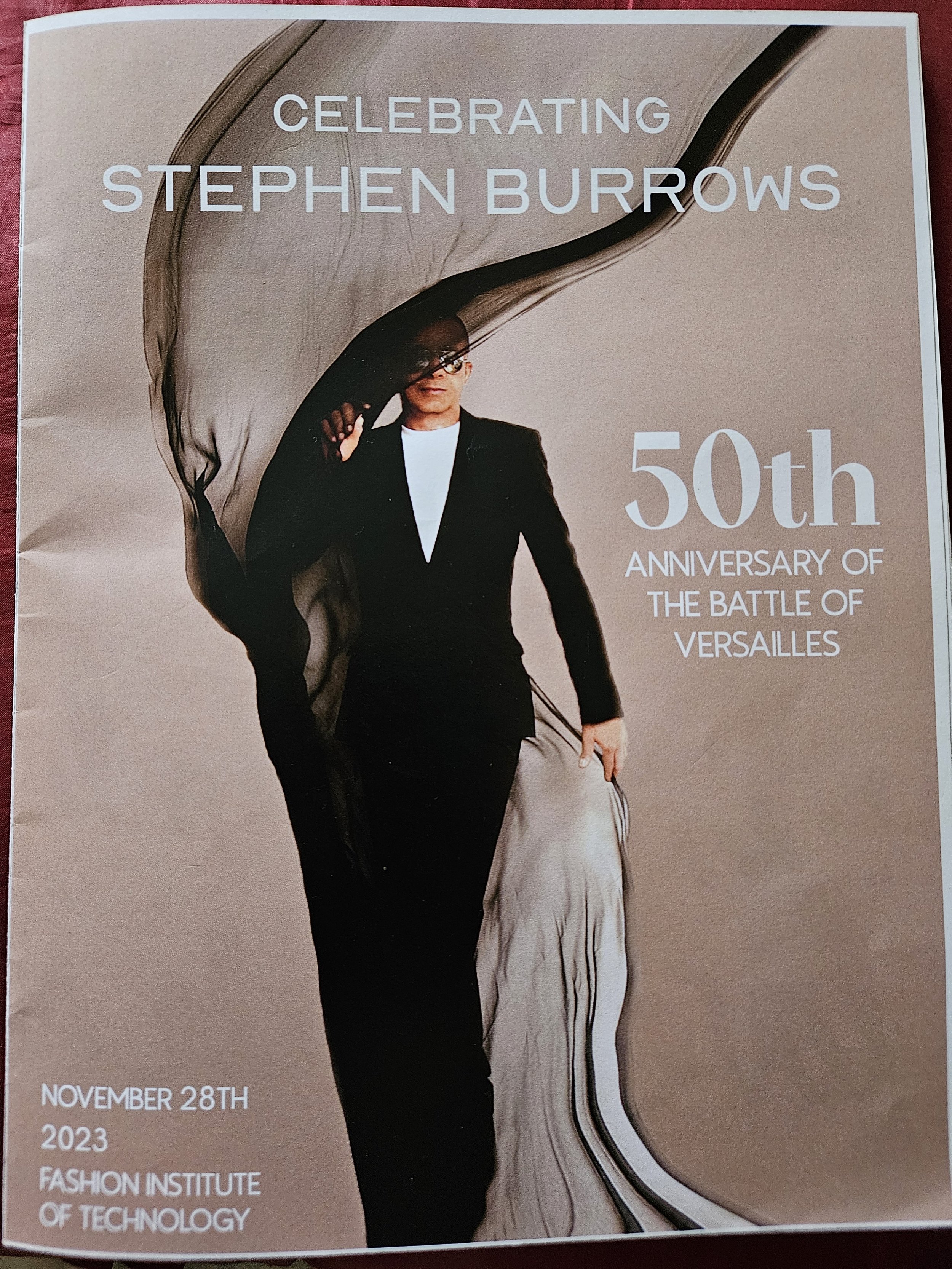

A longtime friend of mine, Denise, recently invited me to attend a tribute for designer Stephen Burrows at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) in Manhattan. A plus size model for decades, she had mentioned Burrows previously in relation to his role and impact on the fashion world and at the so-called Battle of Versailles in 1973—which took the fashion world by storm.

Those who have worked with him across the decades describe him as timeless, a genius, legendary, and someone who approached fashion as a form of art. With a palette of vibrant colors like fuchsia, orange, turquoise, and purple, Burrows was also recognized for his signature asymmetric color block designs, and use of fabric, like jersey, supple and flowing, accentuating the sensuous grace of a woman’s body. Model Carly Cushnie called his designs audacious elegance.

Burrows set his tone and trajectory immediately after graduating FIT: He was one of the first, if not the first designer, to open a storefront in lower Manhattan to showcase his designs; he formed a lasting relationship with the iconic store clothing Bendel’s, where, when he was offered a boutique, he set precedent with an outdoor fashion show on 57th Street, NYC; he was one of the first designers to have his own perfume line; and then there was—as it came to be known—the Battle of Versailles.

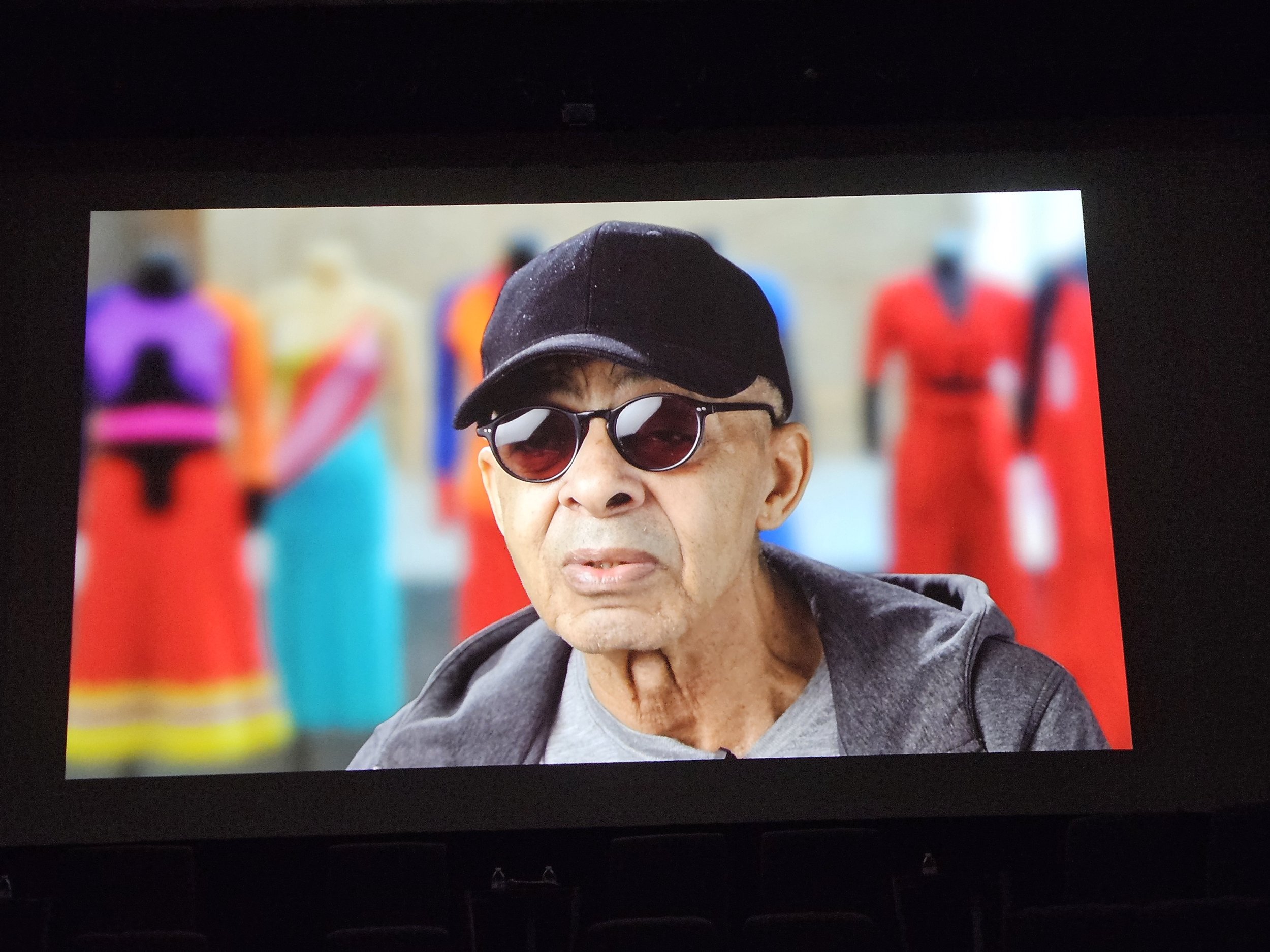

There we were, fifty years to the day of the Battle, applauding Stephen Burrows’ impact on the world of fashion. Through videos, a panel discussion and testimonies, Burrows’ journey unfolded—from his days at FIT to that standout moment in Paris as the only Black-American designer, his models gracing the gold-gilded Versailles theatre in all of its opulence and majesty.

Audacious Elegance at Versailles

Those there tell the story of a monumental event. Initially created as a fundraiser for the restoration of the 17th century Palace of Versailles, it became a news-worthy battle between French and American designers. The French designers included Pierre Cardin, Hubert Givenchy, Yves St. Laurent, and Christian Dior. The American designers were Halston, Bill Blass, Ann Klein, Oscar de la Renta, and an up-and-coming Stephen Burrows.

The tensions throughout the production were evidenced by a litany of issues that plagued the American group, from lack of rehearsal time to no electricity to no food, among other issues. With ample resources, the French created, as expected, an over-the-top two-and-a-half-hour production with a 40-piece orchestra, ballerinas, and enormous, elaborate sets, as well as performances by Rudolph Nureyev and Josephine Baker.

In contrast, the American designers and models had no sets or scenery (due to a metrics/inches debacle) and no dancers. The solo performance was by Liza Minelli. In a thirty-five-minute show, the American models—ten of whom were Black-American—strutted and sashayed to the sounds of Barry White and Al Green. The 700-person audience, filled with celebrities, royalty, and socialites, brought the house down with cheers and foot-stomping as they tossed their programs in the air. A pivotal moment in the fashion industry, the event ignited a shift from the traditional French haute couture style and presentation to a defining moment of liberating movement and a kinetic, energy-filled presentation. It set the fashion industry on fire.

As an American designer, Stephen Burrows is not a household name, but as I left the theater that evening, I better understood why my girlfriend lauded his talent, leadership, and impact in the world of fashion. His vision helped mark a global shift of American influence with ready-to-wear garments and diversity in the fashion industry.

His fearlessness was reflected in the bold color tones and asymmetric patterns that demanded attention and announced an undeniable confidence. What he called “the blood line of the clothes”—red top-stitching on all garments and his "lettuce-edge" hemlines—are signature elements of his style.

He was unafraid to take risks. He courageously created clothes that were sensuous to celebrate women’s bodies and their sensuality.

Burrows empowered the models, affirming their freedom to be fierce and to move with an energy of defiance. Models such as Pat Cleveland, Bethann Hardison, Alva Chinn, and Norma Jean Darden (owner of Spoonbread Restaurant in Harlem), credit Burrows with encouraging a flow and harmony that led them to walk with rhythm—in other words, with an affirmation from their souls.

In a French-dominated industry, Stephen Burrows made a way with a simplicity of presentation, movement as life energy, and sheer joy, giving rise to a transformative moment in fashion history.