The DNA of Eternity: Honoring Wayne Shorter

Wayne Shorter and Esperanza Spalding

Last November, Jewel penned two posts, “Capacity for Caring and Instruments for Change” and “The Art of Creating Space” in which she centered attention on Esperanza Spalding’s collaboration with Wayne Shorter on “Iphigenia,” a reimagining of a Greek myth told by tragedian Euripides.

Jewel wrote:

Finding the heroism in the character lacking in the versions she read, Spalding stepped away from the singular hero narrative fighting impossible odds, to discover the heroic qualities of Iphigenia. Spalding shifted her process to a co-creative circle of other artistic voices for inspiration. The collaborative workshops brought a clarity that prompted Spalding to invite poet laureate Joy Harjo, author and poet Safiya Sinclair, and vocalist Ganavya Doraiswamy to help shape Iphigenia's voice. In recognizing the value of her collaborators’ contributions to fully represent Iphigenia, Spalding made space for them in the telling of the story. I’m excited about seeing this production at the Kennedy Center on December 10th, to experience the amalgamation of many voices becoming one.

The show, which we experienced together with Jewel’s best friend from high school and her mate, was a fascinating operatic rendering of the ritual repetition of tales oft-told, yet with newfound feminine agency, as Spalding’s onstage iteration of Iphigenia wrestled with the imperative to sacrifice or save herself amid powerful forces—military to misogynistic—beyond her control.

The cast of Iphigenia onstage with Wayne Shorter (composer), in wheelchair, and Esperanza Spalding (librettist), second right from Wayne

We left the show on a high and walked out of the Eisenhower Theater upper balcony stage right into the atrium foyer. We decided to take a nearby elevator rather than walk back through the long lobby as we had entered.

We had the elevator to ourselves. The elevator descended a few flights and opened: Wayne Shorter, in a wheelchair, entered along with Frank Gehry, the master architect who created the set designs, and members of Shorter’s band, Brian Blade, John Patitucci, and Danilo Perez.

We were astonished! After greeting them and congratulating Mr. Shorter for the performance, the elevator opened, they departed, and we followed, only to see Esperanza Spalding in conversation with fans. We felt like the moment was made just for us.

Check out the preview video for the show.

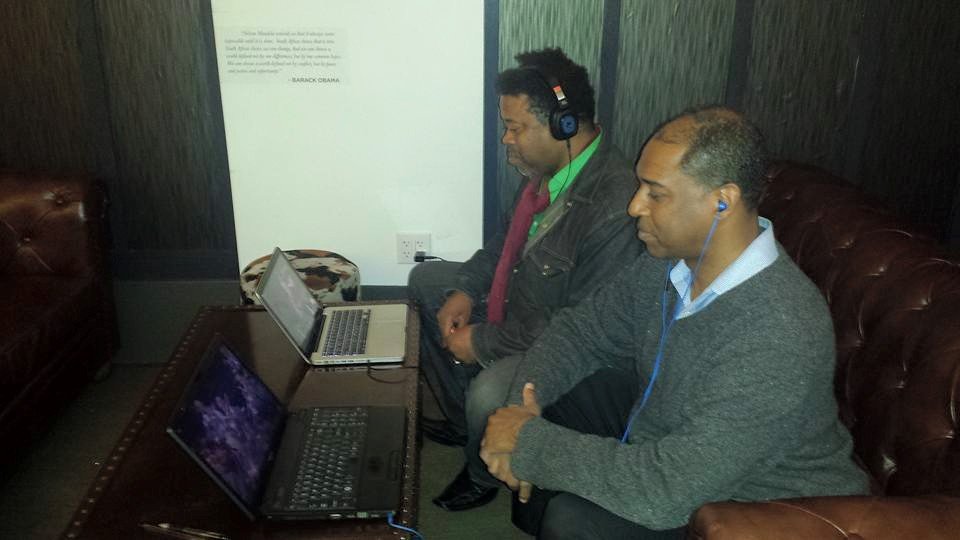

This magical experience was bittersweet for me, as just a few days before my friend and fellow music critic Greg Tate had died. Shorter was a favorite artist of ours. “Whenever Wayne speaks, bruh, time to tune in,” he once told me. “I always want to hear what Wayne has to say.” We vibed on Wayne so much that in 2015 when Shorter performed with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, I attended a rehearsal and then met my fellow mello GT at MIST Harlem to see the webcast of the show.

Here’s an example of what we saw: Wayne Shorter with Wynton Marsalis and the Jazz at Lincoln Center play Shorter’s “Yes and No.”

Wayne’s Quartet a Decade Ago

Ten years ago I wrote a feature story on Shorter in the New York Daily News, a preview of his quartet’s performance in Rose Hall. I share an edited version of that piece here now, in honor of a living grandmaster of jazz:

After 600 shows, the Wayne Shorter Quartet functioned almost telepathically.

“It takes a kind of courage and chance-taking attitude and trust for them to do what they do when we get together, as this combination, myself included,” Shorter said. What the Grammy-winning ensemble did is play without a script, creating music that ebbs and flows, ascends and descends, their improvisational intent creating organic unity in the moment.

Shorter, perhaps the greatest living composer in jazz, can take you around the world in 80 minutes of conversation. High-wire discussions spiral through music, comic books, science, film and philosophy in a seeming blink. Similar to his saxophone playing, Shorter is highly associative, with one phrase or idea leading to another, sometimes directly, at others in sideways patterns or leaps of discursive thought or sounds.

But certain patterns and themes emerge in the life and work of a master artist whose compositions enlivened groups led by Art Blakey, Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock and others in the 1960s, and whose co-leadership of Weather Report in the 1970s helped define the sound of an era.

Brian Blade, Wayne Shorter, Danilo Perez, and John Patitucci

Wayne’s quartet was formed in 2000 with drummer Brian Blade, bassist John Patitucci and pianist Danilo Perez. He told me that he appreciates the different personality and character attributes each member brings to the group. Blade is “one of those kind of people that if you try to find him, you’ve got to be Sherlock Holmes. But when he’s ready to work, and is on the scene, he’s entertaining. He supplies another layer, and he’s another kind of storyteller, continuing the story of life.”

Born and bred in Brooklyn, bassist Patitucci is a devout Christian who teaches at the Berklee School of Music. Shorter takes pleasure in Patitucci’s “writing music for chamber groups and music to lift people’s spirits when he’s at home on the holidays.”

The local transmutes to the global through the Panamanian pianist Perez. “Danilo is involved in humanity,” Shorter says. “He wants everything to go global.” Perez is the artistic director of the Berklee Global Jazz Institute and leads the Panama Jazz Festival as well.

Shorter supports such global initiatives, including his friend Herbie Hancock’s UNESCO declaration of April 30 as International Jazz Day. “[They] eradicate the artificial boundaries and comfort zones that become stifling in the journey of life, comfort zones that become cancerous and epidemic, separating and alienating all manner of people from whatever their roots are,” he said.

“Their roots are joined. The differences in races, ethnicities and nationalities are like the leaves of many trees,” he adds. “But all of the trees in the world are finally connected together, way beneath the earth. And there’s a connection to the universe and space, too; it doesn’t have to be a solid form.”

Shorter was born in Newark, N.J. in 1933. “I had no inclination to be a musician. I was an art major in art high school. I would have comic books all over the place when I grew up. Then it hit me, in hindsight. What got me about Charlie Parker, Miles and Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk was that they represented superheroes to me.”

The influence of Shorter’s sax sound and style from the 1960s on other jazz musicians is rivaled only by Sonny Rollins’ and John Coltrane’s. The three tenor titans also shared a quest for spiritual enlightenment.

In Shorter’s case, he’s a long-standing Buddhist.

He once spoke with Miles Davis about philosophy. “We’d just talk about this stuff just a little bit, and Miles would be in that same zone. Then he’d say, [Shorter imitates Miles’ gravelly whisper] ‘Why don’t you play that?’ I said, ‘Whoa!’ Miles was like that.”

Essential themes in Shorter’s worldview are a belief that endings are an illusion, and the concept of being “in the moment,” which he describes as central to his music.

“Jazz is done in the moment,” he says. “Being in the moment is one of the processes freeing us from fear of the unknown.

“In the philosophy I’ve been involved with, the moment, now, is the only place that you can alter the past and determine the future,” Shorter adds. “In other words, don’t keep living by the past. Be the director, actor, producer of your own life. This is a challenge. Life is the ultimate adventure. The single moment is the DNA of eternity.”