Hemingway, Politics, and Wisdom

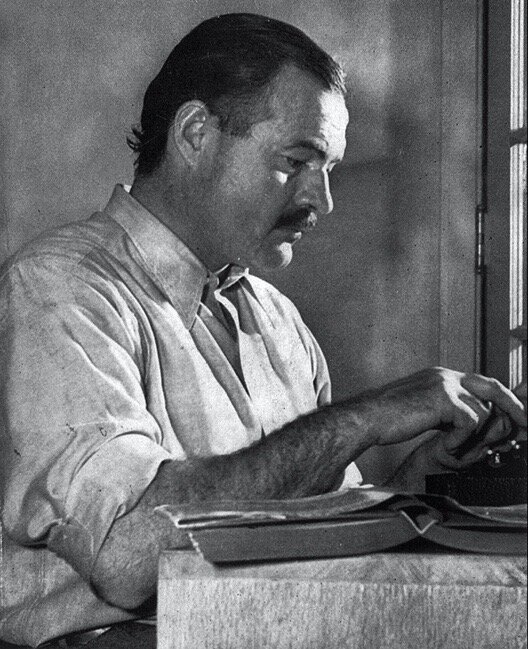

Ernest Hemingway

I think style is more important than political ideologies.

—Ralph Ellison, Conversations with Ralph Ellison, p. 124

I have a distaste for ideologues, folks who advocate for political positions as fervently as some express fundamentalist religious beliefs. In fact, it seems that for many politics is like a religion. Many of not most ideologues are sincere, but their closed-mindedness to other points of view and evidence against their “side” is largely what keeps deep polarization so entrenched. I think this is true, for instance, of both “anti-racist” ideologues as well as “anti-Critical Race Theory” and “anti-Social Justice Warrior” ideologues.

I guess that's why I’m a radical moderate.

These days, the echo chamber of social media leads most to confirm bias through content and online discussion for “us” and against “them.” Ideologies, generally speaking, create political boxes of behavior and conflict. The novel Demons or The Possessed by Dostoevsky is a masterpiece example of the hysteria and passions of ideology and hyperpartisan political action.

. . . I was introduced to The Possessed not in undergrad or graduate school—turns out my informal post-secondary education in the Ellison-Murray Continuum came via one Michael James, a son of Ruth Ellington, nephew to one Duke Ellington. That’s right: DUKE ELLINGTON. Michael James came into my life in the mid-1990s at just the right time, upon the urging of Albert Murray.

On a landline phone with my Mentor, grandmaster Murray, him dropping bombs of wisdom at the speed of light, Michael James’ name came up. Likely tired of discussing certain basics found in literature, lessons he had integrated into his being by the 1940s at the height of the newness of bebop jazz, with me, a neophyte to the true riches of literary wisdom, Murray said of his friend and top intellectual protege: You should call Michael James. He’d kick your ass. Unlike some people masquerading as jazz critics, he actually knew those people.

Michael became a dear friend with whom conversations about jazz, literature, history, the never-ending tale of male-female relationships, and the tragi-comic nature of the human condition occurred on the regular, so much so, in fact, that my first wife grew jealous of our interminable conversations late into the night. Through Michael James, I gained clarity on the timeless value of art and aesthetics over the time-bound world of politics.

For instance, not only did he urge me to read Dostoevsky and Thomas Mann’s works, so we could discuss and apply their insights into the tragic and ironic aspects of life, Michael gave me a graduate school level schooling in the work and thought of Ernest Hemingway. As I was a budding journalist when we met, Michael urged me to read BY-LINE: Ernest Hemingway, a collection of Hemingway’s non-fiction writing from 1920-1954. That one book prepared me for a career in journalism like no other. Classic Hemingway pieces such as “Old Newsman Writes: A Letter from Cuba [Esquire, December, 1934] and “Monologue to the Maestro: A High Seas Letter [Esquire, October, 1935] are must-reads for would-be American writers and journalists. For instance, this classic passage from “Old Newsman Writes” rounds the way back to our theme:

Now a writer can make himself a nice career while he is alive by espousing a political cause, working for it, making a profession of believing in it, and if it wins he will be very well placed. All politics is a matter of working hard without reward, or with a living wage for a time, in the hope of booty later. A man can be a Fascist or a Communist and if his outfit gets in he can get to be an ambassador or have a million copies of his books printed by the Government or any of the other rewards the boys dream about. Because the literary revolution boys are all ambitious. I have been living for some time where revolutions have gotten past the parlor or publishers’ tea and light picketing stage and I know. A lot of my friends have gotten excellent jobs and some others are in jail. But none of this will help the writer as a writer unless he finds something new to add to human knowledge while he is writing. Otherwise he will stink like any other writer when they bury him; except, since he has had political affiliations, they will send more flowers at the time and later he will stink a little more.

The hardest thing in the world to do is to write straight honest prose on human beings. First you have to know the subject; then you have to know how to write. Both take a lifetime to learn and anybody is cheating who takes politics as a way out. It is too easy. [emphasis added]

—Ernest Hemingway

Not that political action isn’t necessary—especially NOW. In democratic societies, voting is a form of civic action citizens can and should exercise to the fullest. If you have issues of deep concern, research and get involved with people and organizations that address them. I’m partial to an organization called SAM, the Save America Movement, and have given them time and money.

But the more you take a 360° view of issues, keeping in mind the wisdom of the ages, and, from my cultural frame of reference, the blues idiom tradition, the more you take politics with a grain of salt. No matter who wins on Nov. 3rd, the nation should survive as long as enough citizens stand for and stand on the democratic ideals found in the nation’s sacred documents: the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. That may sound “old-school” to some, too quaint, but it ain’t. In those documents are the very values that, when and if enacted, could in actuality solve our perennial issues of challenge and conflict.

My Black American ancestors fought hard for freedom and attained it based on the social contract illuminated in those documents. That fact is an ancestral and historical truth, as difficult as life in the United States remains and as much hell as far too many people still catch. Vote, continue fighting, but also smell the roses, be grateful for the life and blood coursing through your veins, appreciate the warm smile of your son or daughter, give thanks for your teachers and honor your parents, hug your friends and beloved. As Albert Murray said on Ken Burns’ Jazz documentary series:

Ernest Hemingway called it ‘the sweat on a wine bottle.’ If you don't enjoy how those beads of sweat look when you pour the white wine out, and you taste it, and how your partner looks, and how the sunlight comes through...you missed it.

—Albert Murray