Guest Post: Stanley Crouch, A Personal Remembrance and Appreciation by Aryeh Tepper

Dr. Aryeh Tepper

Below, my friend and colleague Aryeh Tepper shares his remembrance of our mutual influence, Stanley Crouch. Events move fast in our times; much headlining news has occurred since my own reflections on Stanley a week ago. But we’re leaning into his memory on our newsletter because of Stanley’s centrality to our own grasp of the power of music, writing, ideas, culture, and spiritual insight through conscious culture and artistic beauty. Stanley was a man of many dimensions, containing, as Walt Whitman famously wrote, “multitudes.” In Aryeh’s essay, we discover even more of those dimensions.

Like many of my contemporaries, my main source of spiritual nourishment growing up in the United States during the 1980s was music. I was one of those kids Allan Bloom wrote about in The Closing of the American Mind, the kind who grew up without a tradition or heritage or any book that fundamentally frames their experience, but who had music. As I matured, more and more of that music became jazz. Initially, I was pulled in by Reid Miles' Blue Note covers and Stanley Crouch's liner notes. I stayed for the sound.

Liner notes, an often strange but occasionally wonderful literary genre, is where you went to get "the word" about the music you just bought. Crouch's notes swung with brio and insight in equal measure. I don't remember which Wynton Marsalis or Marcus Roberts disk I had purchased, but either way, Crouch helped me to hear the music – Albert Murray said the critic's role is to mediate between the music and the audience – and I took a master class in writing.

In time, I found Crouch's "Premature Autopsies," the "sermon" from Marsalis' Majesty of the Blues. I derived deep, deep spiritual nourishment from that stunning text and the music that sustained it. The second part of a three-part "New Orleans Function" that mocked the notion of "The Death of Jazz," the sermon was rhythmically and precisely recited by Rev. Jeremiah Wright (politics aside, the man can preach…). Every time I heard Rev Wright recite Crouch's words…

Out there somewhere are the kind of people who do not accept the premature autopsy of a noble art form. These are the ones who follow in the footsteps of the gifted and the disciplined who have been deeply hurt but not discouraged, who have been frightened but have not forgotten how to be brave, who revel in the company of their friends and sweethearts but are willing to face the loneliness that is demanded of mastery…

… it resonated. Deeply. I was, after all, out there, alone in my room and really listening. And I was inspired.

Meeting Stanley Crouch

I finally got to meet and hang out with Stanley on two different occasions. The first time was in March, 2012. I had, in the meantime, become passionately interested in Judaism, moved to Israel, and deeply immersed myself in the Jewish tradition. Back in the States for a two-year post-doc, jazz was no longer my main source of spiritual nourishment, but it remained a teacher, a rough-and-ready reminder that life often consists of swinging through changes – one hopes gracefully − and improvising on the spot. Jazz was a sophisticated yet unpretentious friend, open and generous, and fun to be around.

We met at a Kosher restaurant in Brooklyn. Stanley's idea. He looked around and smiled as we entered. He said he liked service that's salty, particularly when the waiter makes you feel like he or she is doing you a favor by taking your order. I don't remember what we ate but I remember that the service was, indeed, poor and Stanley was, accordingly, happy.

I had come armed with some of Stanley's liner notes and shyly placed them on the corner of the table, readying myself to ask some questions. He saw the notes out of the corner of his eye, ignored both them and the gesture, and completely filled the space of our discussion. Fine with me, as I was happy to be along for the ride. In order to understand Stanley's conversation, I wrote in my notebook after I got home, you need to really listen. You can't understand his conversation the way you understand a usual conversation. He skipped from idea to insight to joke to anecdote to idea, but the implicit connections remained unstated. You had to do the work. It was like having Thelonious Monk as a conversation partner, if Monk was intensely interested in the psychology of police, thugs, and Puerto Rican beauties. He shared ideas and insights and stories that I remember, vividly, until today.

Cops, he said, aren't impressed by resumes. They know that education and money and status are no indication of moral fiber, "at all."

Thugs, he said, are always concerned not to be soft, "It's the dictatorial mindset: I had to do it." In the movies, "murder looks cool. Aesthetic. So hip hop artists can dig it. Scorsese understands that these guys are just thugs."

When he used to teach, he said, he would place a picture of Satchmo next to a picture of Beethoven and ask the class, "Which one do you think is an artist?" Then, "Yeah, but no one's in pursuit of feeling like this (pointing at Beethoven), they're in pursuit of feeling like this."

I discovered that Stanley had a Nietzschean nose for resentment. People, he said, resent great talent. Like Bird. Like Marsalis.

And he shared his idea that Jews and black Americans share a cynical joie de vivre. I just kind of nodded, taking it in. A little nonplussed by my response to his point, I think, he added that [Saul] Bellow liked it.

The second time I hung out with Stanley was at Dizzy's jazz club at Jazz at Lincoln Center. Michael Carvin's quartet was playing, and Carvin's manager at the time, Greg Thomas, was there, together with Paul Devlin. Both Paul and Greg were students of Albert Murray and friends with Stanley. Paul had generously arranged the first meeting, as well as the show.

Michael Carvin, Rhonda Hamilton, Michael Bourne and Stanley Crouch at Dizzy’s Club Coca Cola

There was less talking this time. We all arrived with the intention of digging the music. Still, before the show, Stanley announced that Jews were masters of dissatisfaction. Always wanting to improve things. Perennial critics. He clearly meant it as high praise. The music started before I had a chance to follow up.

Carvin's quartet was cooking that night, and at the end of the show they started playing a little "free." This I'll never forget: Stanley turned his head away from the stage and, with a twang damn close to Steve Urkel, said, "I don't understand what they're trying to express."

After the performance, Stanley generously offered to give me a ride home. On the way, he shared his love of Billy Higgins, the great jazz drummer. Stanley had been a drummer before becoming a writer, so he knew what he was talking about. Billy Higgins, he said, knew how to get with everyone. Whatever anyone else was doing, Higgins was there, on the inside, pulsating with good will, full of sympathetic feeling. I remember thinking, that's a wonderful way to experience music. Later, I came across Stanley's celebration of Higgins in Considering Genius, a brilliant book whose extended opening essay is a wonderful introduction into jazz as music for grown men and women. Looking back, I wonder if Stanley's admiration for Higgins' responsiveness was his way of acknowledging that there are other ways of being in the world aside from his own strong-willed method of procedure, ways that he deeply respected but could never emulate.

Stanley’s Legacy

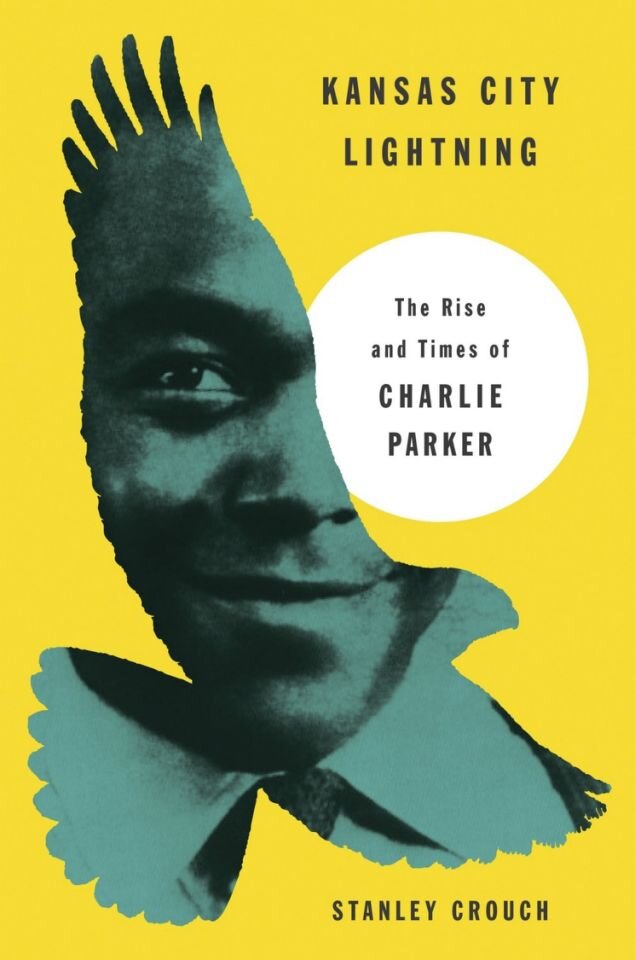

Stanley Crouch's legacy will include his spectacular collections of essays, from Notes of a Hanging Judge to Always in Pursuit. His study of the American regime, "Blues to be Constitutional," in which the separation of powers assumes a blues-like tragic acknowledgment of human frailty, while constitutional amendments preserve the capacity to improvise, deserves to be studied in departments of political philosophy. His novelistic biography of Charlie Parker, Kansas City Lightning, begins with Bird but expands into a panoramic tour through post-emancipation black American culture and history that will last a long time. His novel, Don't the Moon Look Lonesome, most likely will not last a long time, although I enjoyed it. But it's funny, while there are no footnotes in Kansas City Lightning, Stanley added a postscript to the second edition of Don't the Moon Look Lonesome explaining how the book should be read. He was annoyed that the critics didn't get it. Stanley, it seems, either kept his cards close to his chest or shoved them in your face. No Aristotelian middle path for this guy.

But at the end of the day, I keep coming back to those liner notes, and especially to "Premature Autopsies." The "sermon" is a spectacular text, one of the most ambitious and nourishing pieces of wisdom literature written in the past half-century. It's that good. And when put to music by Wynton, it's even better. It includes a great line − "[T]he sound of a cymbal swinging in celebration is more beautiful than the ringing of a cash register" – that can serve as a unifying theme for much of Crouch's thought and writing. After all, his critique of hip-hop was also, at bottom, a critique of crass commercialism trafficking in dour Billy-the-Kid rebelliousness. The alternative? Well, "There are some of us out here who believe that the majesty of human life demands an accurate rendition in rhythm and tune." No less.

Truth be told, Stanley's critique of crass commercialism places him in good company. In his Preface to Turning the Wheel, the great American novelist Charles Johnson champions W.E.B Du Bois' fight against "materialistic (and short-lived) status symbols" in favor of a vision that embraces, "complete advancement… spiritual as well as political, cultural as well as economic." Likewise, Johnson writes, Martin Luther King Jr. "offered… trenchant counsel" against "American materialism." The problem, King wrote, is that, "the means by which we live have outdistanced the spiritual ends for which we live." In my reading, this is Stanley Crouch's proper company. A deeply rooted (black) American tradition that aspires to nobility. To quote again from "Premature Autopsies":

Nobility is always born somewhere out there in the world, and when you live in a democratic nation you have to face the mysterious fact that nobility has no permanent address, you have to face the fact that nobody has nobility’s private phone number. Nobility is not listed in the phone book. Nobility is not listed in the society column, nobility shows up where it feels like showing up, and where it feels like showing up might be just about anywhere. If it could rise like a mighty light from among the human livestock of the plantation, you know it can come from anywhere it wants to. You see, nobility is listed though. Yes, it is listed. Nobility lists itself in the human spirit, and its purpose is to enlist the ears of the listeners in the bittersweet song of spiritual concerns.

Stanley Crouch is gone. May his memory be for a blessing.

May your wishes for Stanley be and become true, Aryeh. I appreciate Aryeh putting thought to pen and fingers to keyboard on behalf of the memory of our friend. I’m especially grateful for his insights on a shining example of Stanley’s work, “Premature Autopsies,” which a jazz critic in the New York Review of Books simplistically reduced to “the fullest expression of Stanley’s work as an ideologue.”

Listen for yourself here. This, I think, is a majestic example of Stanley’s work; Aryeh is spot on above.

I also appreciate Aryeh’s expressed thoughts about me in relation to my course, “Cultural Intelligence: Transcending Race, Embracing Cosmos,” of which I hope Stanley would have given a nod of approval. Here’s what Aryeh had to say:

When I first met Greg eight years ago, I quickly understood that he is a very special person. He uniquely combines a serious commitment to intellectual-spiritual aspirations and concerns with an entrepreneurial spirit. He’s also a wonderful writer and gifted speaker. Whatever the task at hand, Greg not only takes care of business, he does it with a human warmth that makes him a pleasure to be around.

—Dr. Aryeh Tepper, Ben Gurion University

For full details on the course, which starts on October 14, click here.