E Pluribus Unum and the Omni-American Vision

A week ago, we shared a presentation by Zak Stein on democracy and a post-tragic blues sensibility from the first “Shaping an Omni-American Future” broadcast last October. This week we’re featuring my opening remarks for the event, centering on the inspiration for the initiative—Albert Murray.

Thanks so much, Aryeh Tepper, for not only mentioning my phrase, the “blues idiom wisdom tradition,” in which Albert Murray, who coined the term “blues idiom,” is central, but for the many months of work that we’ve put in together to make this event an actuality. Thanks too for the collaborative partnership of the American Sephardi Federation and the Combat Antisemitism Movement and, as well, to all of the speakers participating in, and partners promoting, this broadcast.

Yes, the blues idiom wisdom tradition is key because in our polarized United States and world, we need leadership and wisdom to point the way through the complexity, through the darkness of bigotry and hatred to the generative light of shared understanding and civic values found in the Omni-American perspective. One way of describing this rooted and cosmopolitan point of view is what Murray might have called an “extension, elaboration, and refinement” of the very motto of the United States, E pluribus unum, “out of many, one,” which Chloe Valdary mentioned in her short reading from Murray’s first book, The Omni-Americans.

The Omni-Americans has had at least two subtitles in its various printings since 1970. The first was “Some Alternatives to the Folklore of White Supremacy.” The second was “Black Experience & American Culture.” Let’s delve briefly into these subtitles and explore Murray’s life and career, simultaneously.

In the first, unlike many today who intone white supremacy as an all-inclusive indictment, Murray’s characterization made clear what that ideology actually is: folklore, a folk belief, in this case, a lying tradition of invidious customization of racist domination and exploitation, passed on from generation to generation. That belief system is still held by some today, for sure. But if we look across American history, from indentured servitude of so-called whites and blacks, to Bacon’s Rebellion and the subsequent legalization of racialized groups to insure that the planter class wouldn’t face the kind of collaboration that this very event represents, the American Revolution and independence from the British monarchy, the Civil War and Reconstruction, and the Jim Crow period to now in 2021, can we really say that white supremacy is as prevalent as in those days?

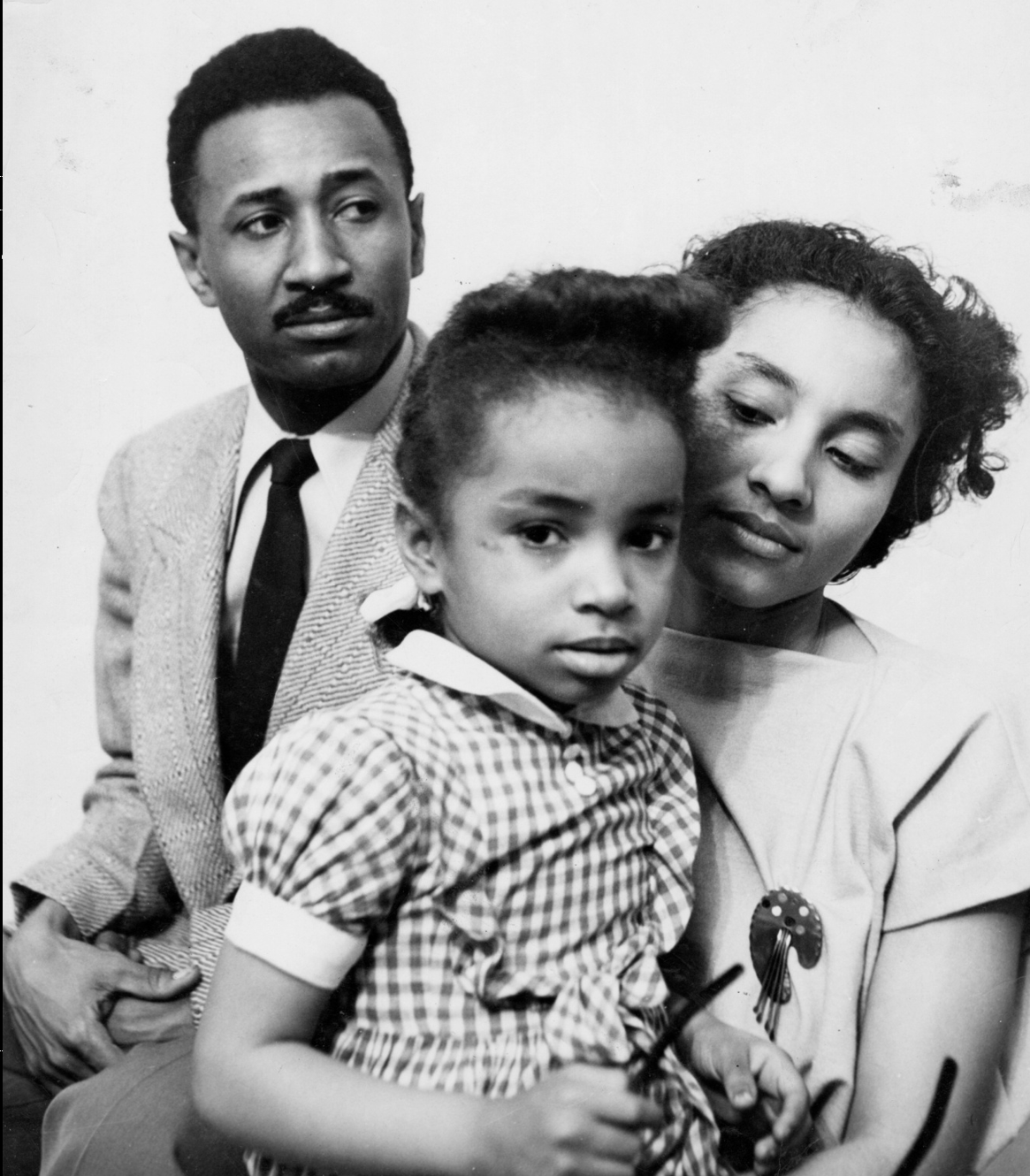

I respectfully contend that nowhere near the amount of people today hold on to the folklore of white supremacy as part of their identities as when Murray was born in Mobile, Alabama in 1916 and adopted by Hugh and Mattie Murray. Or when he was voted the best all-around student at the Mobile County Training School, and awarded a tuition scholarship to attend Tuskegee Institute in 1935, where he graduated in 1939, or when he married Mozelle Menefee, who herself graduated from Tuskegee in 1943, the same year Murray enlisted in the United States Army Air Forces and that their one daughter, Michele, was born.

The folklore of white supremacy, truth be told, was far more prevalent when Murray re-encountered, in 1942, Ralph Ellison, an upperclassman at Tuskegee when Murray was an undergraduate. That year they began a lifelong personal and literary friendship, which you can learn more about by checking out their collection of letters from 1950-1960, Trading Twelves. In those days of social infamy, we were still, especially in the South, living under the thick, racist heat of the Jim Crow regime when Murray met his hero Duke Ellington in 1946, the same year he ended World War II active duty, transferred to the Air Force Reserve, and returned to Tuskegee to teach.

Even during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s, where Black American and Jewish American collaboration for justice became a shining example for this very event, the folklore of white supremacy was more salient than now. That shining period is also when Murray began publishing fiction and non-fiction as a professional writer, which he devoted himself to full-time after retiring, with the rank of major, from the Air Force.

Our broadcast over the next two days focuses on the power of culture through intellectual, artistic, moral, and spiritual excellence. Our gathering together is a complement and continuation of what began in the Civil Rights movement, and even earlier in jazz.

The second subtitle of The Omni-Americans, “Black Experience and American Culture,” alludes to the centrality of the experience of Black Americans to American culture, and for far more than our horrific experience of enslavement. In fact, if we combine the insights of Orlando Patterson in his magnificent work, Freedom in the Making of Western Culture, with the brilliance of political philosopher Danielle Allen in Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship since Brown v. Board of Education, we can conclude that freedom in the West generally, and in America specifically, was the tragic central value and generative core that inspired the heroic sacrifice that Black Americans made and continue to make to insure that we move closer to the realization of the principles in our creed.

Patterson wrote that freedom constitutes for the West, “the germ of its genius and all its grandeur, and the source of much of its perfidy and crimes against humanity.”

With—we hope—nuance, precision, and deep feeling, we’ll return to variations on these themes again and again, as we endeavor to combat racism and antisemitism by shaping, together, an Omni-American future.