Culture vs Race: The Problem and Promise of Values

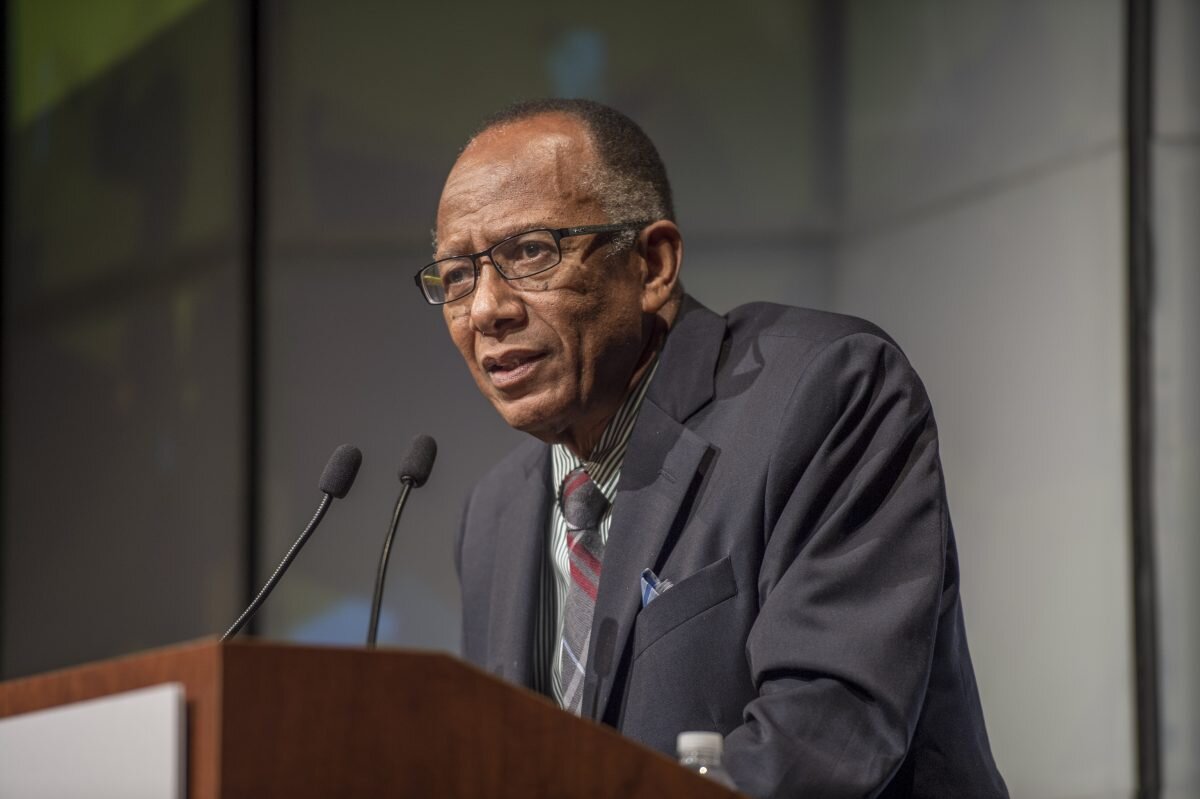

Orlando Patterson, Sociologist and Historian of Ideas

Two months ago, I published a polemic, “Culture vs Race: American Identity Hangs in the Balance.” Today’s essay will be more analytical and less polemical. One purpose of this exploration is to investigate the underlying idea of race, upon which racism, whether seen in personal or institutional forms, rests. Another is to view culture as a potential counterpoint and counterstatement of race, with benefits accruing to more people in their everyday lives. We’ll also see that race and culture intersect in the realm of values. This recognition points to problems and possibilities as we struggle to untangle the gordian knot of race.

With that intro in mind, let’s go.

Historical and psychological research has shown that a suspicious or negative view of "others" different from one's group seems to be a universal cognitive response among humans. Our neurology biases toward perceiving threats and dangers because way back in the day—human hunter-gatherer stage—our very lives depended on being alert to dangers in the natural environment. This bias became what we call xenophobia (fear of strangers), and is also tied to ethnocentrism, the favoring of one’s own ethnic group over others. The attitudes and practices underlying the expression of xenophobia and ethnocentrism in large part constituted how race came to be used in the United States.

A Short Natural History of the Race Concept

As mentioned in the companion essay, race is a slippery, shape-shifting idea in existence for just a few hundred years. Before the modernity—say the European Enlightenment to the late-1950s—race was used to classify groups of people, but wasn't as tied to physical and phenotypic characteristics as in the past few centuries. Language, custom, religion, status and class were more important than physical appearance to categorize groups based on difference before the modern period.

The biologist Richard Dawkins famously coined the term “meme” to equate cultural ideas that spread among people with the way genes work within biology. The meme of race is what post-modernists call a "social construction," a social invention used to categorize others and justify social and economic domination. The Genome Project and other recent scientific research has proven that race, a socio-political construction, is not based on genetic origin or biological essence.

Yet, even though we now know that race isn’t essentially biological, early scientific research in the 18th, 19th, through the middle 20th century not only equated race with biology but used scientific rationale to explain why certain groups were "inferior" to others. Along with justification from religious texts, such pseudo-scientific propositions justified chattel slavery, Jim Crow and other forms of social and material domination inscribed into law. Add caste and the growth of industrial capitalism to this stew and we end up drinking a toxic brew that became “the folklore of white supremacy.”

If human “races” evolved based on the "survival of the fittest," as Herbert Spencer argued in the 19th century, then we can understand why those at the bottom of the social totem pole are there. His “Social Darwinism” adaptation of the theory of evolution is an example of a conflation of distinct categories—individual, cultural and social—that plagues us to this very day.

Let’s dig deeper.

The European Enlightenment led to the ideas of liberty and natural rights as universal human values—in theory. Abstract ideals such as democracy, freedom, and equality were all foundational principles to the founding of the American nation, yet, ironically, those salutary values were equated with whiteness and measured by the extent to which blacks and others not considered "white" were not free and equal.

In the Winter 2011 issue of Daedalus, the quarterly journal of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the late Amherst College Professor of American Studies Jeffrey B. Ferguson had an essay titled, "Freedom, Equality, Race." He said:

From their inception, the concepts of freedom and race have reinforced each other in the making of modernity; they continue to do so today, though the concept of race has shifted in its definitional grounding, from nature to culture...the post-civil rights concept of race relies on values, modes of signifying, and behavior.

Herbert Spencer conflated biology, race, and social hierarchy; today, as mentioned in the companion essay, culture and race are confused. To continue to comprehend how race has spread its weed-like branches to the cultural realm, let's look at "culture" as an idea proper.

Culture: Variations on a Theme

For many of us, the first time we recall hearing about culture was when we cultivated bacterial cells in Petri dishes in biology class. By extension, then, culture is a kind of environment. Another analogy would be that water serves as the culture fish live in. It's a natural environment to the fish, whereas our culture is the natural inner environment of collective feelings, values, myths, and the sympathetic resonance we have in common with others we identify with.

Culture is also meanings, tools, and artifacts that manifest in our pragmatic interactions with others. In How Culture Works (1995), the late anthropologist Paul Bohannan detailed how culture "emerges from life just as life emerges from matter" and defined culture as a combination of the tools and the meanings that expand behavior, extend learning, and channel choice.

The late anthropologist Clifford Geertz once defined culture as "an ensemble of stories we tell about ourselves." The economy of that definition is elegant; relating a fundamental human practice such as storytelling with "ensemble," a word allusive to music and the performing arts, appeals to an aesthetic sensibility. Yet let's continue with other descriptions so the weight of our cultural tone can become thick and textured.

Ken Wilber places culture in the Lower Left of his Integral four-quadrant map of human reality. In A Brief History of Everything, Wilber writes that the cultural "refers to all of the interior meanings and values and identities that we share with those of similar communities, whether it is a tribal community or a national community or a world community. And 'social' [Lower Right quadrant] refers to all of the exterior, material, institutional forms of the community, from its techno-economic base to its architectural styles to its written codes to its population size, to name a few."

In 1963, Ralph Ellison described a "cultural complex": "I'm talking about how people deal with their environment, about what they make of what is abiding in it, about what helps them to find their way, and about that which helps them to be at home in the world. All this seems to me to constitute culture."

From the kinship, comfort and security of being “at home in the world," the internal compass implied by "what helps them to find their way" to the ultimate values of "what is abiding in it" as well as the personal and interpersonal response to social reality ("their environment"), Ellison crafted an interpretation of culture clear in common sense tonalities while maintaining fidelity to the term's anthropological origins.

The Promise and Problem of Values

But what happens when “race” becomes a personal and social value? It places its tentacles into culture. Most of us consider values as positive, the important ideas that we share with others, that become basis for how we evaluate matters of ultimate import or just particular things we like or dislike. But values can be negative also.

Max Weber described “ultimate or final values, in which the meaning of existence is rooted.” In “The Nature and Dynamics of Cultural Processes,” Harvard sociologist Orlando Patterson explains:

Ultimate values are prototypic evaluations of the desirable or undesirable: individualism, the work ethic, love of God, nation, and family on one hand, and negative ultimate values such as anti-Semitism, racism, and homophobia, which may be as foundational as favored ultimate values. . . Racism, for example, was a foundational value of the Old South, right down to the middle of the twentieth century.

—Orlando Patterson

If the very meaning structures of individuals, and the explicit and implicit norms within structures of institutions are embodied and embedded with the concept of race, then culture has been infected, with racism the invidious result.

In future essays, as well as in a nine-week course I’m teaching on “Cultural Intelligence” beginning on October 14 (details to come), we’ll pursue a range of approaches to deconstruct race from culture and reconstruct culture as ultimate meaning and a tool to better extend, elaborate, and refine the infinite game of life.