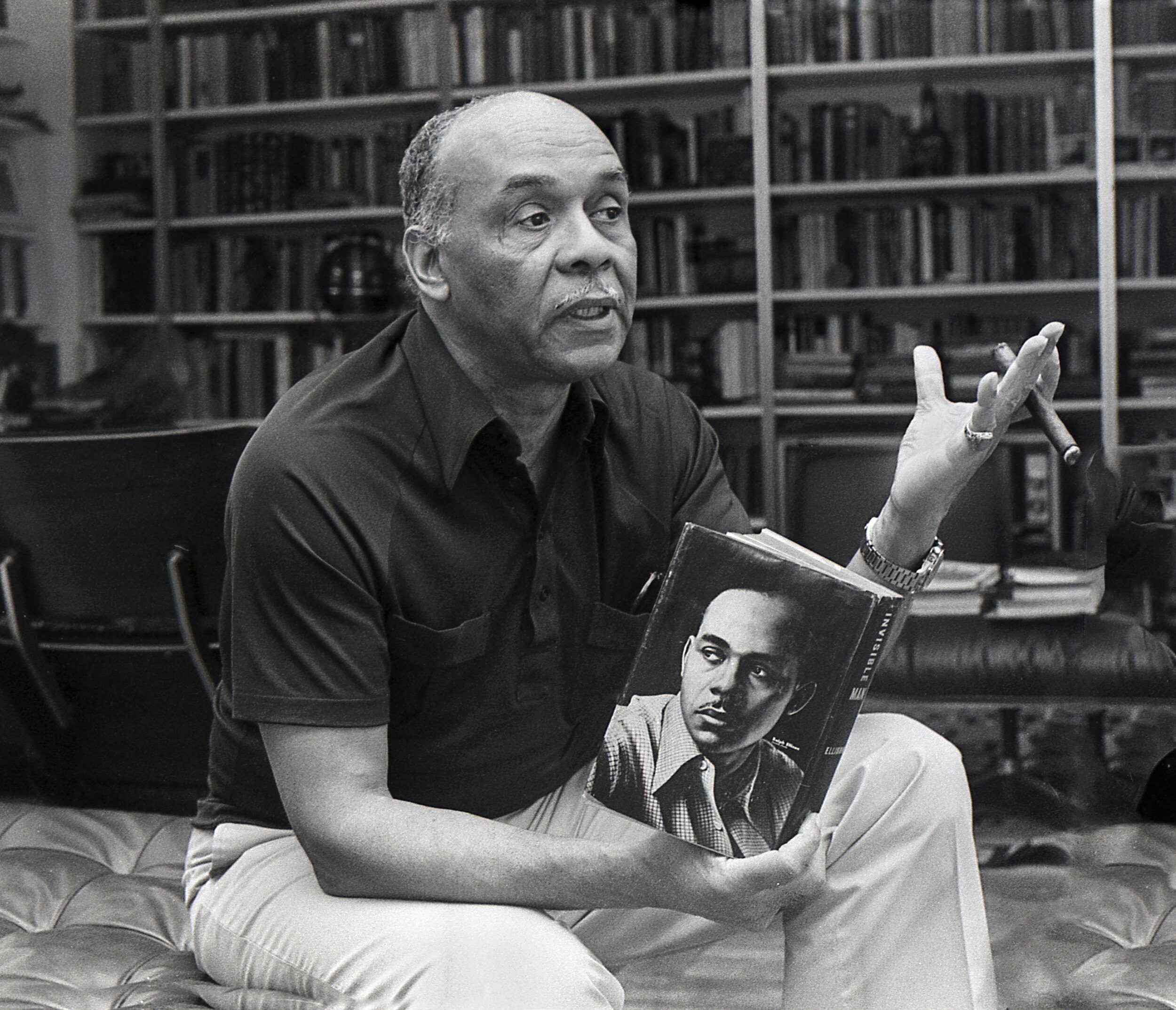

Calling on the Ancestors: The Gift of Ralph Ellison

When during an improvisation a jazz musician quotes from a different song or, especially, from another great artist’s solo, to me that’s more than just a nice allusion. For me, that practice takes on the feeling tone of a ritual.

Such gestures I refer to as calling on the ancestors.

In the confusing, topsy turvy, bizarro times in which we live, with pandemic health risk, social unrest and uncertainty, and the decimation of small businesses, I feel it’s time to do more than make passing reference to the great writers and thinkers of yesteryear. If we are grappling with perennial issues and ongoing problems, as well as unique predicaments—and most certainly we are—then great writers and thinkers have too.

What might they have to contribute to our moment?

If we have ears to hear and eyes to see, they can help us through this crass morass of confusion. Because the time is dire and the possibility of downfall great, it’s time to call on the ancestors.

That’s why I thank the Ralph and Fanny Ellison Charitable Trust for giving me permission to quote from our revered ancestor Ralph Ellison, in detail, in his own words. As his main man Albert Murray would say, what follows is an “extension, elaboration, and refinement” of the ideas I presented in my “Culture vs Race: American Identity Hangs in the Balance” essay last week.

As you read, recall that Ellison spoke in the idioms of his generation and his time (“Negro American” and use of masculine pronouns). But don’t get it twisted and miss the forest for the trees. What’s most relevant is the timeless eloquence and wisdom of an American genius, arguably the most profound theorist of American culture of the 20th century. The extended quotes below, originally published between 1958 and 1979, are taken from several classic interviews, reviews or essays among many you’ll find in his peerless nonfiction. They all can be found in the Modern Library’s essential The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison.

As you would with a five-course meal prepared by a master chef, I urge you to savor every bite and morsel that follows.

Ellison on Race, Cultural Idiom, and American Possibility

“We differ from certain white Americans in that we have no reason to assume that race has a positive value, and in that we reject race thinking wherever we find it. And even this attitude is shared by millions of whites. Nor are we interested in being anything other than Negro Americans. One’s racial identity is, after all, accidental, but the United States is an international country, and its conscious character makes it possible for us to abandon the mistakes of the past.

The point of our struggle is to be both Negro and American and to bring about that condition in American society in which this would be possible. In brief, there is an American Negro idiom, a style and a way of life, but none of this is inseparable from the conditions of American society, nor from its general modes or culture—mass distribution, race and intra-national conflicts, the radio, television, its system of education, its politics.

If general American values influence us; we in turn influence them—in speech, concept of liberty, justice, economic distribution, international outlook, our current attitude toward colonialism, our national image of ourselves as a nation. And this despite the fact that nothing which black Americans have won as a people has been won without struggle. For no group within the United States achieves anything without the asserting its claims against the counterclaims of other groups. Thus, as Americans we have accepted this conscious and ceaseless struggle as a condition of our freedom, and we are aware that each of our victories increases the freedom for all Americans, regardless of color.

When we finally achieve the right of full participation in American life, what we make of it will depend upon our sense of cultural values and our creative use of freedom, not upon our racial identification.”

From “Some Questions, Some Answers” (1958)

Ellison on Slavery, Desire, and “What We Had in Place of Freedom”

“Slavery was a most vicious system, and those who endured and survived it a tough people, but it was not (and this is important for Negroes to remember for the sake of their own sense of who and what their grandparents were) a state of absolute repression.

A slave was, to the extent that he was a musician, one who expressed himself in music, a man who realized himself in the world of sound. Thus, while he might stand in awe before the superior technical ability of a white musician, and while he was forced to recognize a superior social status, he would never feel awed before the music which the technique of the white musician made available. His attitude as ‘musician’ would lead him to seek to possess the music expressed through the technique, but until he could do so he would hum, whistle, sing or play the tunes to the best of his ability on any available instrument. And it was, indeed, out of the tension between desire and ability that the techniques of jazz emerged.

This was likewise true of American Negro choral singing. For this, no literary explanation, no cultural explanation, no cultural analyses, no political slogans—indeed, not even a high degree of social or political freedom—was required. For the art—the blues, the spirituals, the jazz, the dance—was what we had in place of freedom . . . . whatever the degree of injustice and inequality sustained by the slaves, American culture was, even before the official founding of the nation, pluralistic, and it was the African’s origin in cultures in which art was highly functional which gave him an edge in shaping the music and dance of this nation.”

From Ellison’s review of Leroi Jones’ “Blues People” (1964)

The Timbre and Texture of Black American Experience

“It is not skin color which makes a Negro American but cultural heritage as shaped by the American experience, the social and political predicament, a sharing of that ‘concord of sensibilities’ which the group expresses through historical circumstance and through which it has come to constitute a subdivision of the larger American culture.

Being a Negro American has to do with the memory of slavery and the hope of emancipation and the betrayal by allies and the revenge and contempt inflicted by our former masters after the Reconstruction, and by the myths, both Northern and Southern, which are propagated in justification of that betrayal. It involves, too, a special attitude toward the waves of immigrants who have come later and passed us by.

It has to do with a special perspective on the national ideals and the national conduct, and with a tragicomic attitude toward the universe. It has to do with special emotions evoked by the details of cities and countrysides, with forms of labor and with forms of pleasure, with sex and with love, with food and with drink, with machines and with animals, with climates and with dwellings, with places of worship and places of entertainment, with garments and dreams and idioms of speech, with manners and customs, with religion and art, with life styles and hoping, and with that special sense of predicament and fate which gives direction and resonance to the Freedom Movement.

It involves a rugged initiation into the mysteries and rites of color which makes it possible for Negro Americans to suffer the injustice in which race and color are used to excuse without losing sight of either the humanity of those who inflict that injustice or the motives, rational or irrational, out of which they act. It imposes the uneasy burden and occasional joy of a complex double vision, a fluid, ambivalent response to men and events which represents, at its finest, a profoundly civilized adjustment to the cost of being human in this modern world.”

From “The World and the Jug” (1963-‘64)

Ellison on Cultural Diversity and Democracy

“… it would seem that for many our cultural diversity is as indigestible as the concept of democracy in which it is grounded. For one thing, principles in action are enactments of ideals grounded in a vision of perfection that transcends the limitations of death and dying. By arousing in the believer a sense of the disrelation between the ideal and the actual, between the perfect word and the errant flesh, they partake of mystery. Here the most agonizing mystery sponsored by the democratic ideal is that of our unity-in-diversity, our oneness in manyness.

Pragmatically we cooperate and communicate across this mystery, but the problem of identity that it poses often goads us to symbolic acts of disaffiliation. So we seek psychic security from within our own inherited divisions of the corporate American culture while gazing out upon our fellows with a mixed attitude of fear, suspicion and yearning.

We repress an underlying anxiety aroused by the awareness that we are representative not only of one but of several overlapping and constantly shifting social categories, and we stress our affiliation with that segment of the corporate culture which has emerged out of our parents’ past—racial, cultural, religious—and which we assume, on the basis of such magical talisman as our mother’s milk or father’s beard, that ‘we know.’ Grounding our sense of identity in such primary and affect-charged symbols, we seek to avoid the mysteries and pathologies of the democratic process.”

From “The Little Man at Chehaw Station” (1977)

Ellison on American Culture as a Whole: The Homeness of Home

“. . . within an area of our society which has been treated as though it were beyond the concerns of history, the democratic process has been made to operate by dedicated individuals—at least on the level of culture—and that it has thus helped to define and shape the quality of the general American experience. Which is something that those who were charged with making our ideals manifest on the political level were not doing. But fortunately, American culture is of a whole, for that which is essentially ‘American’ in it springs from the synthesis of our diverse elements of cultural style.

It is the product of a process which was in motion even before the founding of this nation, and it began with the interaction between Englishmen, Europeans, and Africans and American geography. When our society was established, this ‘natural’ process of Americanization continued in its own unobserved fashion, defying the social, aesthetic and political assumptions of our political leaders and tastemakers alike. This . . . was the vernacular process, and in the days when our leaders still looked to England and the Continent for their standards of taste, the vernacular stream of our culture was creating itself out of whatever elements it found useful, including the Americanized culture of the slaves.

In this sense the culture of the United States has always been more ‘democratic’ and ‘American’ than the social and political institutions in which it was emerging. Ironically, it was the vernacular which gave expression to that very newness of spirit and outlook of which the leaders of the nation liked to boast. Such Founding Fathers as Franklin and Webster feared the linguistic vernacular as a disruptive influence and sought to discourage it, but fortunately they failed, for otherwise there would be no Mark Twain.

They failed because thanks to the pluralistic character of our society, there is no way for any one group to discover by itself the intrinsic forms of our democratic culture. This has to be a cooperative effort, and it is achieved through contact and communication across our divisions of race, class, religion, and region. In the past the cultural contributions of those who were confined beneath the threshold of social hierarchy—which is to say outside the realm of history—were simply appropriated without credit by those who used them to their own advantage. But today we have reached a stage of general freedom in which it is no longer possible to take the products of a slave or an illiterate artist without legal consequence.

Today the vernacular artist knows his value, and thanks to our increased knowledge of our cultural pluralism, such artists are identified less by their race or social status than by the excellence of their art. Our awareness of what we are culturally is still inadequate, but the process of synthesis through which the slaves took the music and religious lore of others and combined them with their African heritage in such ways as to create their own cultural idiom continues . . .

Through the democratizing action of the vernacular, almost any style of expression may be appropriated, and today such appropriation continues at an accelerating pace. . . In this country it is in the nature of cultural styles to become detached from their places of origin, so it is possible that in their frenzy the [white] kids don’t even realize that they are sounding like Black Baptists. As Americans who are influenced by the vernacular, it is natural for them to seek out those styles which provide them with a feeling of being most in harmony with the undefined aspects of American experience. In other words, they’re seeking the homeness of home.

In closing, let me say that our pluralistic democracy is a difficult system under which to live, our guarantees of freedom notwithstanding. Socially and politically we have yet to feel at ease with our principles, and on the level of culture no one group has managed to create the definitive American style. Hence the importance of the vernacular in the ongoing task of naming, defining and creating a consciousness of who and what we have come to be.

Each American group has dominated some aspect of our corporate experience by reducing it to form; thus we might well make a conscious effort to seek out and explore such instances of domination and make them our conscious possession. I say ‘conscious’ because in pursuing our democratic promises, we do this even when we are unaware. What is more, our unwritten history is always at work in the background to provide us with clues as to how this process of self-definition has worked in the past. Perhaps if we learn more of what has happened and why it happened, we will learn more of who we really are, and perhaps if we learn more about our unwritten history, we won’t be so vulnerable to the capriciousness of events as we are today. In the process of becoming more aware of ourselves we will recognize that one of the functions of our vernacular culture is that of preparing for the emergence of the unexpected, whether it takes the form of the disastrous or the marvelous.”

From “Going to the Territory” (1979)

Please let us know what you think and feel about this five-course meal of Ellisonia that we’ve prepared as a gift for you. If the meal was both tasty and nourishing—to extend the metaphor—please share it with others.