Albert Murray on the Roots of American Studies

Cultural and civic leadership is a common theme of our writings here at Tune In To Leadership. Yet, as is the case with becoming and being a top-notch jazz musician, there is much preparation and deliberation required to do it well. In my case, the preparation for such leadership as co-founding the Jazz Leadership Project and becoming co-director of the Omni-American Future Project involved decades of study and deep conversations.

For instance, of my many conversations with Albert Murray only one has been released publicly, in the volume Murray Talks Music: Albert Murray on Jazz and Blues, edited by scholar Paul Devlin, with a foreword by the writer and cultural critic Gary Giddins and an afterword by yours truly. This conversation, taped when Murray was 80 years old, was a part of my going “deep in the shed” to study American life, history, and culture. In retrospect, I was preparing to, as Ralph Ellison urged, take “personal responsibility for democracy,” as an American citizen with a keen awareness of the ancestral and Omni-American imperatives of those who sacrificed for me and the nation long before my existence, and others, such as my daughter, Kaya Thomas, who can continue contributing to the lineage now and after my eventual departure.

The italicized portion directly below was my intro to the interview in the volume, followed by the first excerpt, which I gladly share with you, our readers.

I had known Albert Murray for several years before I entered the doctoral program in American Studies at New York University. I called Mr. Murray on a spring day in 1996 and mentioned that I had entered the program—at his graduate alma mater—and was doing a lot of new reading. Subsequently, I wanted to get his take on some of the things I was reading, and I had some questions for him. He said, “Okeydoke, come on by.”

Visiting him was an exciting experience but never without a certain amount of trepidation. He could be testy and short if you hadn’t done your homework. Yet he could tell I was a sincere apprentice writer, and he knew by then that I had studied his works, under the guidance of his protégé, Michael James. Murray’s knowledge of the discipline of American Studies was vast and relayed effortlessly. Knowledge about the early years of the discipline that was then being excavated was as fresh in his mind as the morning’s headlines.

I wanted to get clarification of his principles as I worked on my own synthesis of disparate materials in cultural studies and theory. As you’ll see, he gave such clarification and more, as he ties music into the discussion. — Greg Thomas

GREG THOMAS: At what period would you say the study of American culture, per se— a stream of thought that you tie into— began?

ALBERT MURRAY: From the point of view of criticism I would think it started by the 1920s. People like Lewis Mumford: Sticks and Stones, The Brown Decades. The artists were doing it— Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Malcolm Cowley— those people became more American by going to Paris. They weren’t running from American culture. That’s what Malcolm Cowley points out in his book Exile’s Return. They … were on the Seine dreaming about “The Blue Juniata” [a poem by Malcolm Cowley and the title of the first successful commercial song written by an American woman]. Guys that didn’t go were also interested in basic principles of literary criticism. Like Kenneth Burke; he stayed in New Jersey.

GT: You also have people like Randolph Bourne and Van Wyck Brooks.

AM: Yeah, but Van Wyck Brooks was at first lamenting it— there’s a lot of difference between the Van Wyck Brooks of The Pilgrimage of Henry James, The Ordeal of Mark Twain, America’s Coming-of-Age, and stuff like that and the Van Wyck Brooks of “Makers and Finders” [series of books]. What had come in between was Constance Rourke!

There was a guy named Paul Rosenfeld. Waldo Frank. Lewis Mumford. Some guy named Weaver. They didn’t discover Moby Dick until the 1920s. Between the late [eighteen] nineties and the 1920s, nobody cared about Herman Melville. You had people beginning to look. You had a self-consciousness on the part of intellectuals as well as the artists. The artists were ahead of them. See, Twain was already there. But they didn’t appreciate Twain, and, you know, William Dean Howells and all these people. It came into a certain type of critical focus by the twenties. Meanwhile, the stuff was already there, so far as the arts were concerned. Henry James was over in London, but he was an American. It was an American sensibility with all the refinements and so forth. But that is part of America—to be European and American and whatnot.

In one of her books, Constance Rourke points out, in The Roots of American Culture: that’s the moral of the thing. By the end of the thirties, Van Wyck Brooks was into his romance of American literature: The Flowering of New England, New England: Indian Summer, The Times of Melville and Whitman, The World of Washington Irving, and The Confident Years: 1885-1915, which brings you into the teens. He was fascinated by how this thing came together and made a beautiful—

GT: Tapestry?

AM: Story. It’s the romance of American culture. “Oh yeah, Audubon— that is American culture.” The Birds of North America—that’s where it is. Constance Rourke, she’s studying the almanacs and stuff like that. It wasn’t until after World War II that you could actually take courses in American Civilization. There was American history, American literature, there were anthologies. We had our classics: Longfellow, Holmes, Hawthorne, Emerson. And they stand up. Longfellow slipped. We think of him as like, maybe kids’ stuff. Hawthorne is still adult. You wouldn’t find a group of very sophisticated literary critics having a big, serious seminar on [Longfellow’s] “The Song of Hiawatha.” I mean, I don’t think so, you know. Basically, you think “Americans should have read that,” but in grade school or high school. That didn’t happen to The Scarlet Letter, The House of Seven Gables, and things like that. It didn’t happen to Emerson’s essays. F. O. Matthiessen calls it the American Renaissance. Whitman was in by this time. Academically, we didn’t get to it until the forties or fifties.

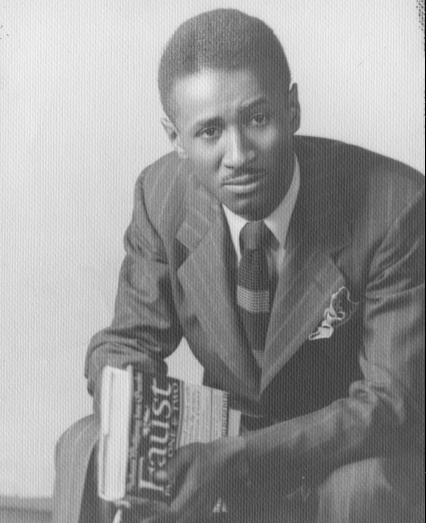

Albert Murray circa 1939, as a student of literature and culture

GT: Put in the contribution of anthropology also. After all, Constance Rourke was influenced by and was even friends with Ruth Benedict, who was a student of Franz Boas.

AM: The basic study of culture is going to always lead you to that. Aesthetic extension of that would be how it looks in the fine arts. But all these things are coming out of the way of life of the cultural configuration that you have in mind. That’s where I started in the eleventh grade [at the Mobile County Training School] when I discovered anthropology. I wanted to know: “where did art come from?” and “what was the function of art?” I could see these things better when I looked at them anthropologically. I could see society on a simpler level. You could see where the fundamentals were.

You’ve got what the Marxists were calling the superstructure. You’ve got the elaborations of it, but you’ve got to look down in there and see what’s under it: the ritual. That takes you back to the primordial stage, to the real fundamentals. Other people get all extended out there and they don’t know what people are really doing. They just latch onto what they know about it. They come in on the level of the way of doing something— which, of course, is convention. Most people experience life through the convention that they inherit. The conception of the world and everything is the convention . . . What enables you to find the convention, to isolate and define it, would be the anthropological elementals. You know my book Stomping the Blues? What is it about? It’s ritual. The primitive ritual; it’s either a ritual of purification or fertility. You can’t get more fundamental than that. I define the blues in terms of getting rid of the blues, which is why everybody else is wrong, so far as I can see. Yeah, he may be talking about this, but what do people do at a juke joint? You don’t go there to pray about “Oh, how terrible it is to be a Negro!”

GT: [Laughter]

AM: It has nothing to do with that. The white folks didn’t say, “Yeah, those poor Negroes.” Bessie Smith went through a lot, but if she missed that note, it doesn’t matter what she went through. A lot of people were worse off than Billie Holiday. But she mastered [the form]. She can’t just say “I had it in me”—that’s bullshit— she’s imitating Louis. It’s derived from something. Art comes from art. Art does not come from life. Nobody looks out there and all of a sudden, he’s an artist. People say that, but they forget. You’re an artist because there are [other] artists. You join in the ongoing dialogue with the form. You can’t get Charlie Parker, for example, until you get Kansas City blues, the Kansas City approach to blues. That’s why he’s up-tempo to begin with! If he was with the traditional down-home blues, he wouldn’t have been up there— he wouldn’t have moved up to a higher interval. He’s got to get to Basie and [Lester] Young and Sweets [Edison] and Buster Smith and he wants them to listen. He’s trying to communicate! Here’s [Papa] Jo Jones up here [imitates uptempo Jo Jones drumbeat] and he wants to swing up there. Anybody who doesn’t know that doesn’t know anything about Charlie Parker.

Now, technologically, you could make him aware of conservatory abstractions, “Oh yeah, I could do this, I could do that”— to refine your mechanism, but those are just refinements. You wouldn’t expect a guy to come out of New Orleans or the Delta or various other places and play up there where Charlie Parker did. Once it’s out there, they’re imitating him! They’re not doing it because they’re musicians, they’re doing it because Charlie Parker was a musician. That’s why you get [Billy] Strayhorn—he’s doing it because Duke [Ellington] did it that way. But because he’s not Duke, he’s gonna sound a little different. It’s very easy to tell Duke from Strayhorn. So all this bullshit they got about Duke and Strayhorn— that’s bullshit. You couldn’t get anything in the band without Duke revising it. Then, he’s gonna be playing it every night. It’s his music. But you gotta see that dynamic underlying all of it. It’s a combination of those things that you like, approve of, and attempt to extend, elaborate, and refine in your own way—or that you feel the necessity to counter-state, but it’s still a dialogue.

GT: Right.

AM: You can say, “Well, Murray and Ellison . . .” Yeah, but Murray’s over here kickin’ Baldwin’s butt! So Baldwin is influencing me as much as Ellison.

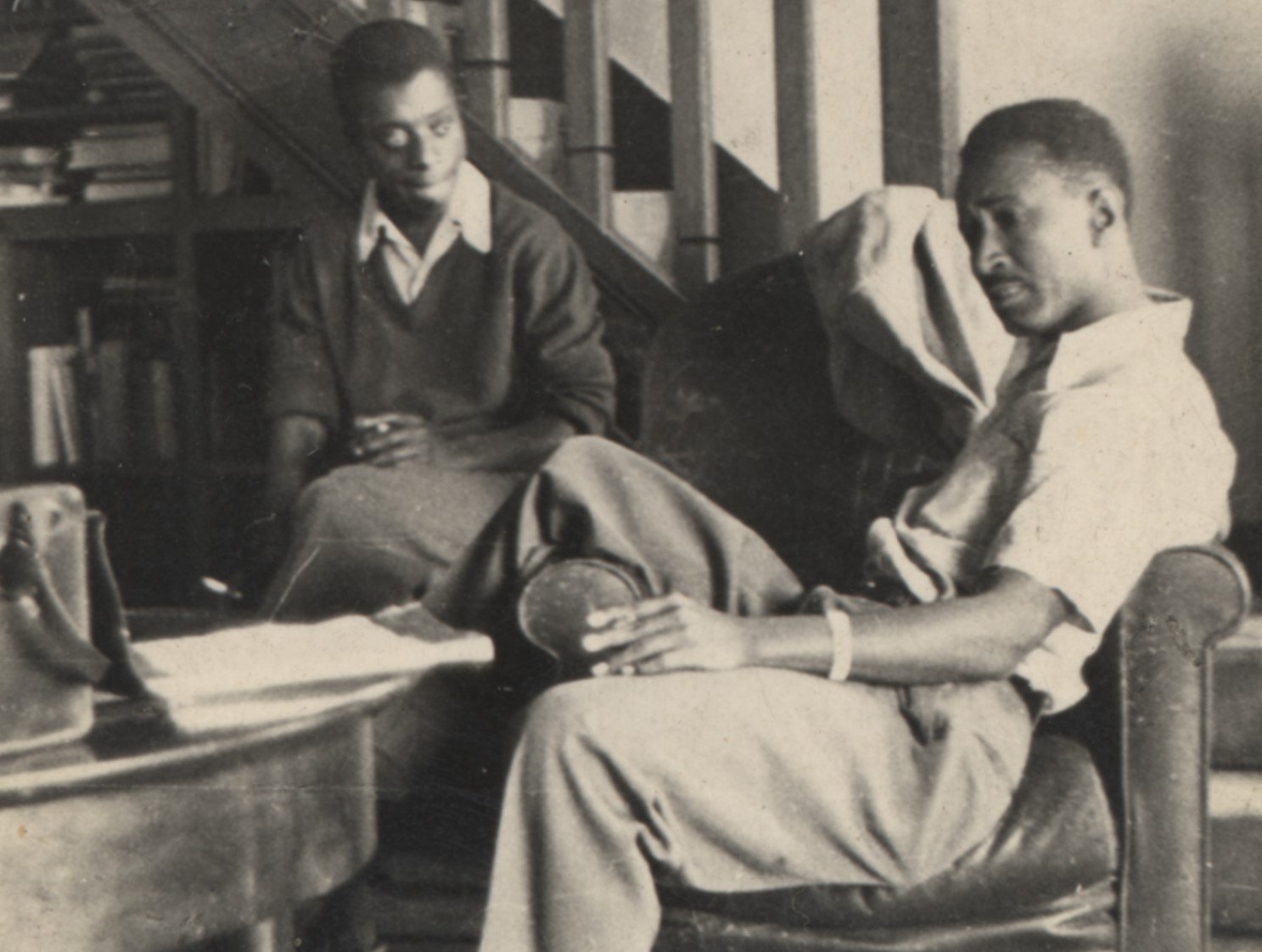

James Baldwin and Albert Murray in Paris, circa 1950

GT: Ooooh. Wow. I see what you’re saying.

AM: It’s a counterstatement. I wouldn’t have said that [Murray’s essay on James Baldwin in The Omni-Americans] if he were not there. What would I have said? I don’t know what I would have said! I had some conceptions, but Baldwin brought them into a sort of focus. I said, “That ain’t the way that is. What is this? I can’t stand that! I’m not a victim. I never felt like a victim!” I always thought I was smart, good-looking, and promising. That’s what I always thought. That’s what people always said. “Look at that honey-brown boy. He’s so nice. He’s so smart.” That’s the way I was brought up . . . .

GT: Could you go a little deeper into the concepts of folk art, popular art, and fine art?

In our next excerpt from this 1996 interview, Murray provides musical examples to answer the question above, dives deeper into the foundations of Constance Rourke’s thought, relates his own work to Mark Twain’s, riffs about his cinematic conception, and much more.