Albert Murray: “Human Consciousness Lives in the Mythosphere”

Albert Murray, Greg Thomas, and Sidney Wertimer at Hamilton College on the occasion of Murray receiving an honorary degree in 1997

What follows is the last of three excerpts—here’s part one and part two—from an interview with my mentor and friend Albert Murray in 1996, a conversation that Murray scholar Paul Devlin said is most indicative of the free-flowing, widely-ranging conversations that Murray would often have when speaking informally. When Murray really got going in informal conversations, for hours on end, it was like the difference between Charlie Parker’s recordings in a studio with time limitations and when “Bird” stretched out in a club, such as the Live at Birdland date—check out the first solo on the recording; Murray’s conversations, as John Edgar Wideman once said, were like the “runaway, star-climbing notes of a Charlie Parker solo.”

In retrospect, there are so many follow-up questions I wish I could ask him, not only regarding statements in this interview—some that would be controversial today—but about so much more. Yet his own books, interviews, secondary scholarship, and the memories of those who knew and loved him will suffice for now. As a hat tip to him, I invite you into the mind and heart of a 20th-century genius and raconteur par excellence, Albert Murray, followed by some final, critical remarks as an out-chorus.

Greg Thomas: Just to ask you about [Ralph] Ellison for a moment—the second novel—what he shared of it with you, would you say that it went beyond Invisible Man in achievement?

Albert Murray: It depends on what you mean by “beyond.” It was a different kind of book. I don’t know. I saw quite a bit of it, but I never knew what the overall form was gonna be. I didn’t have an idea of what the major climax would be. He read a lot of it to me, and he sent me some drafts of certain sequences. But I wouldn’t speculate. It had a lot of possibilities. More than one hundred pages of it were published. Probably quite a bit more than one hundred pages—but you couldn’t make it out from there. The difficulty of bringing it off was not a matter of barrenness. It’s not that he had writer’s block and couldn’t think of something to do. That’s not it. He’d bring in a character, he had to justify putting this character in, and he would start inventing stuff to make this character fit into the place where he was gonna be. That frequently got out of hand. The guy would take over. I don’t know for how long—weeks or months. All he had to do was get the guy from one floor to the other—pushing a medical cart or something in a hospital.

The senator, who got shot with a zip gun, is on one floor. And Ralph decides to put Ezra Pound in St. Elizabeth’s. So, he got a guy named Sterling—Pound Sterling [“Clyde Sterling” in the 2010 published version]—a poet who’d been committed for insanity or something. He wants to connect these two characters in some way. So he’s got a guy pushing a medical cart. The guy becomes fascinating to Ralph. He grows into a big fat character—all he had to do was get the guy from one floor to another. You could just cut. It would be an indulgence to use five or ten pages to do that. He’d be lucky if it was thirty. More likely it would be seventy-five. So, it wasn’t a conventional conception of a writer’s block. The problem probably is that there was too much manuscript. I wouldn’t be surprised if it could be well over a thousand pages of manuscript.[i]

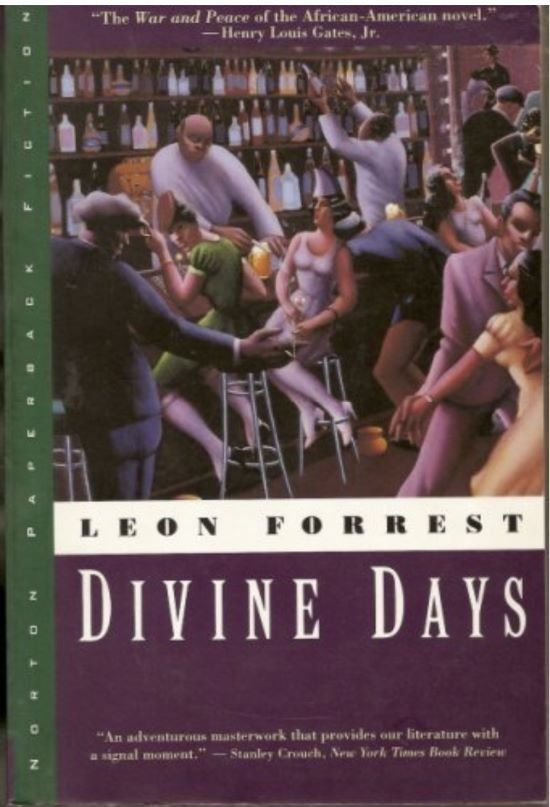

GT: Speaking of long manuscripts, what do you think of Leon Forrest’s Divine Days?

AM: I haven’t had time to read it. Ralph’s reaction was that Forrest, you know, should have been more . . . coherent?

GT: Tighter?

AM: Tighter. But he was impressed with his imagination and his use of language. He was very favorably disposed to Forrest’s ambition and his talent. I think he thought it should have manifested more of a discipline than it had—it was almost like an indulgence. Ralph may have been aware that he had a similar problem—but he wasn’t gonna publish it! He was a very sensitive type of person to criticism—that just meant that he was a highly disciplined person. He wasn’t defiant, he just felt very strongly about it and felt it was worth taking a chance on, and that he was right and other people were not. And you have to be like that to be an individual artist. You’ve gotta do it your way, in a way. Somebody may think they know what a novel is, but they don’t know what this kind of novel is necessarily.

GT: I was wondering what you thought of Derek Walcott’s work.

AM: In some ways he’s an outstanding modern poet. That’s because he plays in the same league as first-rate poets. He knows what that is about and he’s trying to find his voice in it. But he doesn’t shuck on it. He knows what contemporary poetry is. . . I’ve wished I had time to do Omeros. But I’ve dipped into it, and I know it’s big-league stuff. I saw a couple of his plays a long time ago. I know he’s a real student of whatever he does. I think he wrote a play called Dream on Monkey Mountain. And then he did a thing called Remembrance [& Pantomime], which I saw, with Roscoe Lee Browne in it, at the Shakespeare Theater. I don’t know if [in that play] he was being somewhat critical of himself for being too British. I get the impression that he wants to create an image of ambivalence because he doesn’t know whether he’s British or African. But he isn’t African—he’s West Indian.

I didn’t go through all the poetry. I have quite a bit of it, and I plan to. I have high regard for his level of ambition. But the thing I like best that he did was his Nobel lecture! There he comes up with a Caribbean identity that makes a lot of sense to me. “They’re not us and we’re not them, we’re not African and we’re not British—we’re Caribbean!” You see? But you can take what Negroes are doing in education in one state and wipe out all the islands. There is more institutional educational achievement in Georgia than any of those islands. Tennessee? Texas? They achieved that beginning with Reconstruction. What the hell was Marcus Garvey doing over here? Trying to be a Booker T. Washington. He wanted to be the Booker T. Washington of Africa! [laughter] But then Walcott reveals the other dimension.

I was really delighted that [in the Nobel lecture] he accepted the challenge of Saint-John Perse. Alexis Saint-Léger Léger. He is the Caribbean poet—but he’s a Frenchman! T. S. Eliot introduced his work to the world of English poetry. This is the kind of thing you have to deal with. [reads extensively from the poetry of Saint-John Perse]

GT: What about the work of Soyinka? Have you read or seen any of his plays?

AM: Did he give them in the early days of the Ensemble Theater?[ii]

GT: I’m not sure. He’s another one who, with that training in Europe, tries to maintain a native African sensibility.

AM: I never developed much interest. I didn’t have any cultural relationship. Since I’m not a racist, I wouldn’t identify with that. I don’t have any particular connection with Nigerian culture. If he had a bigger impact that was related to literature and not race relations, then probably I would have some interest. But because a guy’s got nappy hair and dark skin . . . I don’t give a goddamn about that! I was pleased to see that Walcott is aware of the sweep. You can feel the epic sweep. That’s what you get in Perse’s Anabasis. Walcott’s got this big conception, a man-against-the-horizon-type thing, with desert and seascape, vistas and things like that.

GT: Can you explain something you explained to me the other night when I asked you how things went when you got that award? What’s the name of the organization you got the lifetime achievement award from?

AM: The National Book Critics Circle [The Ivan Sandrof Lifetime Achievement Award].

GT: Congratulations again on that. You mentioned the mythosphere. What’s the mythosphere?

AM: Well, it’s the ideational equivalent to the atmosphere. You live in terms of ideas, notions, words, lies, truths, mistakes, anything—that makes up the mythosphere. The atmosphere is oxygen and this and that. Human consciousness lives in the mythosphere—that could be anything from mathematics to a flat-out lie. Anything that has to do with human consciousness. Today I have a problem with my leg because of the humidity and so forth—that’s a physical condition of the atmosphere. The mythosphere has to do with the quality of human consciousness.

The piece of paper says “We honor Mr. Murray for lifetime achievement in literature.” To me, that says “Here’s a man who’s gonna do big-league stuff!” If you don’t read books and you don’t care about books, it means nothing to you. Here’s where we go with that: the big problem in the mythosphere is that people mistake very flimsy constructions of publicity as the real mythosphere.

Literary criticism helps your insight into these things. If you think of yourself as somebody developing a more sophisticated taste on a higher level of aesthetic profundity, you’re more careful about what comes into your consciousness—publicity is not enough. You don’t go out and read a book because it’s number one on the best-seller list. There is a less sophisticated part of the mythosphere.

GT: That would be the pop level of the mythosphere?

AM: That’s the level of sophistication involved in the response. It’s just like the sensitivity of the body to the atmosphere.

[i] According to John Callahan and Adam Bradley, the editors of Ellison’s unfinished second novel, Three Days Before the Shooting, it was several thousand pages.

[ii] When the Negro Ensemble Company opened in Greenwich Village in 1967, they staged a play by Wole Soyinka, Kongi’s Harvest.

Out-Chorus

As I re-read the words and thoughts above, I realized that his admonition that “publicity is not enough” may have been an extension of his critical (and some might say short-sighted and unfair) remarks about Wole Soyinka. Soyinka won the Nobel Prize in 1986, six years before Derek Walcott did. But Murray was impressed far more with Walcott’s apparent “epic sweep” and high literary aspirations, evidenced by his work and his Nobel lecture, than with Soyinka’s work, his Nobel lecture, and its more apparent political and racial edge.

Murray’s standards were nigh aristocratic, and he didn’t lower them for anyone, certainly not based on some supposed “racial” tie, or even what today is called an African “diasporic” perspective. Yet while I appreciate and share Murray’s pride in the accomplishments of our idiomatic Afro-American ethnocultural group, I’d say that in several places above he evinces an ethnic chauvinism that I today, at the age of 60, don’t share. For instance, if we analyze the education level, in terms of literacy rates, of West Indians from Barbados, from whence my beloved wife Jewel hails, I doubt that the moribund public school education in the Southern (and other) parts of the U.S. will compare favorably.

But considering the love and respect I maintain for Murray as a revered ancestor and a profound influence on my outlook, these differences amount to quibbles.

And now, to fully extend and elaborate on the title above, I’ll share a quote from Murray’s essay, “Me and Old Uncle Billy and the American Mythosphere”:

Thus what William Faulkner’s avuncular status with me comes down to is precisely the role of the literary artist in the contemporary American mythosphere, a term that I am appropriating from my friend Alexander Eliot. In other words, there is the physical atmosphere of planet Earth which is said to extend some six hundred miles out into space in all directions and consists of the troposphere in which we live, and beyond which is the stratosphere, beyond which are the mesosphere, the ionosphere, and exosphere.

The mythosphere is that nonphysical but no less actual and indispensable dimension of the troposphere in which and in terms of which human consciousness exists, and as we all know, the primary concern of all artistic endeavor is the quality of human consciousness, whether our conception of things is truly functional, as functional as a point or moral of the classic fables and fairy tales. But that is quite a story in itself. Let me just say that I assume that the role of the serious literary artist is to provide mythic prefigurations that are adequate to the complexities and possibilities of the circumstances in which we live. In other words, to the storyteller actuality is a combination of facts, figures, and legend.

The goal of the serious storyteller is to fabricate a truly fictional legend, one that meets the so-called scientific tests of validity, reliability, and comprehensiveness. Is its applicability predictable? Are the storyteller’s anecdotes truly representative? Does his ‘once upon a time’ instances and episodes imply time and again? I have found that in old Uncle Billy’s case they mostly do.

—Albert Murray, in From the Briarpatch File: On Context, Procedure, and American Identity