R.I.P. Pat Martino: Jazz Avatar

And by climbing upward, I was no longer subject to being altered by that pendulum. So that’s as general and as simple a way I can try to define exactly what I feel about perspective, and how I see life itself and decision within it.

—Pat Martino

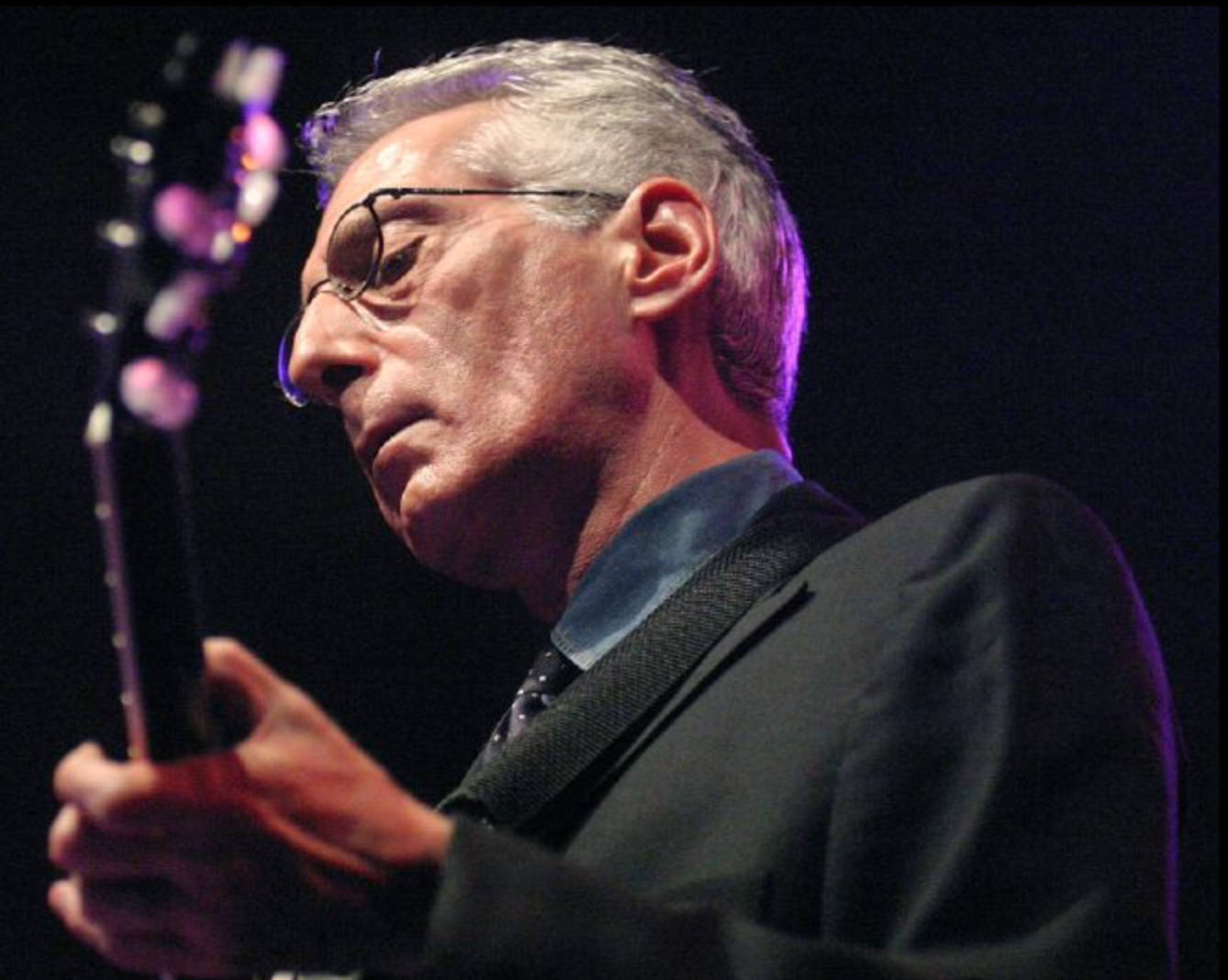

A little over ten years ago, on July 21, 2011, the New York Daily News published my feature story on Pat Martino, long, by then, a legendary jazz guitarist. His death last week at the age of 77 shook me; I loved him and his playing. I first met Pat by chance in Harlem on 135th St. and Lenox Avenue. I had just finished teaching a jazz course at Thurgood Marshall Academy. When the car pulled up and I saw it was him, I had to say something. Like other jazz heads into bebop and beyond, I considered Pat Martino a jazz god.

That moment was captured in the feature documentary film, Martino Unstrung.

The story mentioned above, a version of which follows, was titled: “Jazz Guitar Legend Pat Martino Recalls Moving to New York for Cultural Awakening, Losing Memory.”

Whenever jazz guitar legend Pat Martino played in the Big Apple, it was a homecoming.

“I love every time I come to New York City. I left my hometown of Philadelphia at the age of 15, and this was my home for 27 or 28 years,” he said back in 2011.

Martino is a legend for more than his speed-demon virtuosity at high-velocity tempos or his angelic harmonies on ballads. He has also faced death several times and tells the tale of his survival and recovery with a perspective akin to a Zen master.

Martino began playing guitar at 12, advancing through feverish practice and deep play, as well as exposure to giants such as Wes Montgomery in local joints his dad would take him to — and music lessons with Dennis Sandole, where he’d run into John Coltrane, who would treat him to hot chocolate as they discussed music.

“When I came to New York City in the early 1960s, my main intention was to participate, and take my place within the social culture that surrounded jazz,” he says. “And that’s exactly what took place.

“I went up to Harlem, to what used to be called 135th and Seventh Ave., to Small’s Paradise, which now is an IHOP. These things, for a youngster at that age, were dreams come true.”

A story from the 1960s suggests how much his dreams were realized.

“I invited Les Paul to join with me at Small’s Paradise, primarily to introduce him to Wes Montgomery,” Martino says. “I brought Les into the city, and in between sets at Small’s I walked with him to Count Basie’s club, where Wes was performing that evening.

“I left Les Paul there with Wes, who was a big fan. In fact, they were fans of each other by that point. At the end of the evening, which in those days used to be at about 4 a.m., I left Small’s Paradise with my instrument and walked down a couple of blocks to 133rd to Count Basie’s. The club was emptying out, and outside of the club were Les Paul, Wes Montgomery, George Benson, and Grant Green. The five of us went over to Well’s restaurant, which was famous for fried chicken and waffles and stayed open all night long.”

His organ trio concept started early, with organ stalwarts such as Charles Earland, Don Patterson, and Brother Jack McDuff. By his early 30s, he was a recognized master guitarist around the world. But in 1976, he began having massive seizures.Martino didn’t yet know it, but he suffered from an abnormality of blood vessels in the brain called AVM, or arterioevenous malformation. His behavior became odd, and he was even institutionalized for a short time. By 1980, he had a life-threatening brain aneurysm that required immediate surgery. The successful operation had a horrific side effect: Martino lost his memory.

To regain his equilibrium and maintain sanity, he relied on his old recordings, and began learning to play again from scratch.

Asked to describe this process, Martino explained:

“I would describe it as similar to a ship beginning to sink. And the only thing that is there to grasp, to cling to for survival in this ocean of confusion, is one object. That is what the guitar became for me. It took my mind off very distorted perspectives. Until finally, the instrument itself became an extremely rewarding experience with regards to the creative process, which amplified my sensitivity in the midst of insensitivity.

“By doing so, it brought my intentions to the forefront in such a way that it demanded definitive decisions and choices.”

Greg: Can you give an example?

Martino: I can give you an example by a picture. And the picture in mind I would propose for you to see is of a pendulum moving from left to right, and an individual standing beneath it. If the individual remains located in that stable position, that individual is subject to being touched and cut by this pendulum. The pendulum represents positive and negative, good and bad, all the things that move from one side to the other on a constant basis. The one thing that these experiences brought about to me was a decision to no longer stand in one place. And whenever it went to a negative side, instead of feeling that negativity, I found ways to climb upward, over where I stood prior to that decision. And by climbing upward, I was no longer subject to being altered by that pendulum. So that’s as general and as simple a way I can try to define exactly what I feel about perspective, and how I see life itself and decision within it.

He didn’t view his ordeal as a good or bad thing.

“I see it as an accumulation of many, many things that were necessary for me to reach this stage of development,” he reflected. “And I see everything in it as extremely valuable.

“At this point, I am very happy that everything that took place did so, because the end result is the enjoyment of life, and a deeper respect and devotion to faith itself.”

Martino returned to the professional music scene in 1987 with the album The Return. From that time, he continued to play, record and tour globally. His illness and recovery were the subject of a 2008 documentary by U.K. filmmaker Ian Knox, Martino Unstrung.

He told his life story to award-winning jazz journalist Bill Milkowski. In October [2011], the story of Martino’s life and music career, Here and Now, was released by Backbeat Books.

“I think one of the key lessons of Pat’s story is perseverance,” said Milkowski. “After all the misdiagnoses … after subsequent brushes with death and subsequent hospitalizations — including as recently as 1998 — he’s still living in the here and now. He does precisely that every day, both in word and deed. It’s an inspiring tale that has taught me to appreciate each day, each moment a little more.”

Interview Excerpt

Greg: How do you now view the role of music and jazz in particular?

Martino: I review it constantly with regard to its application. I’m doing a master class for MANR—Music as a Natural Resource—I see music in light of this particular context, to see its use for learning, for traumatic relief, and for health care, and for many other facets of application.

To be able to do and participate in something like this—I think any individual who has devoted himself to any art for long periods of time, either he or she has absorbed the standard of that particular method of communication to a degree that its second nature to them. And by doing so, then they can utilize that opportunity to communicate, to activate things needed that are manually possible. To bring into play, to interact socially and culturally, and to bring to the forefront things that are needed to do, as opposed to sitting back, and being completely absorbed in a craft. It’s no longer a craft at that stage of development. By then it’s second nature. It goes to a level of application that is much broader than the instrument itself. The instrument then takes its place with all of the other instruments that are functionally valuable to any individual.

Greg: How do you feel about your autobiography coming out in October?

Martino: It’s exciting because it’s coming to fruition. The interaction with Bill Milkowski was extremely beneficial with regards to things that were very demanding, in terms of shape and position. It was like being fluid and poured into different glasses and demanding one to take the shape of anything that he or she was poured into. And that’s what the autobiography as an experience turned into. It caused me to re-evaluate and re-experience quite a number of states of mind that I recalled for some time back that had been elusive. It made things concrete. It brought some things to the forefront things that were very valuable as observations on that particular trip, that path.

In honor of Pat Martino, I invite you to check out two clips and one very revealing production featuring him discussing his career and philosophy. The first is his version of “Days of Wine and Roses” from his 1976 recording Exit, a rendition that I’ve listened to hundreds of times. The second is a video of a live performance of his trio swingin’ hard and sweet at the same time on Sonny Rollins’ “Oleo.” Finally, I urge you to check out a short film with the same title as the biography, “Here and Now.”

An avatar of jazz guitar, Pat Martino’s place in jazz history and American culture is indelible. The musical clips in the para above make that clear. And his integration of spiritual wisdom and knowledge of the function of polarity into his conception of life and music made him a soul messenger of the 20th century and beyond. May you have the ears to hear Pat Martino’s message . . . Jewel and I heard it many times and have been enriched and edified at the core of our being.

The last time Jewel and I had the honor of experiencing Pat Martino in person, at The Jazz Standard in New York City.